Historians trace the first use of asphalt all the way back to 625 B.C., where a king's procession used it as a road building material. Today, in the U.S. alone, the national highway system includes approximately 160,000 miles (257,495 kilometers) of roadway [source: U.S. DOT]. That number doesn't even take into account local streets, roads and parking lots.

Next time it rains, take a moment to look outside at your street or parking lot. Do you see how the rainwater tends to pool up near the curb and run toward the sewer? During heavy storms, you can see and even hear floods of water rushing into that sewer, taking everything in its path. We call this runoff. Runoff not only contributes to flooding and erosion; it also plays a part in the contamination of our water supply.

Advertisement

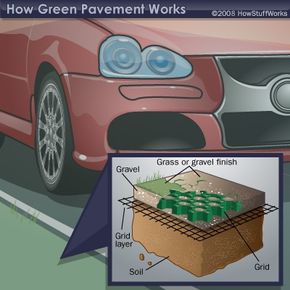

Runoff occurs because traditional pavement is nonporous -- meaning it doesn't allow rainwater to settle back into the ground. Green pavement, a relatively new concept in green building, is a permeable and porous pavement (try saying that three times fast) that absorbs rainwater instead of repelling it. It allows water to return to the ground, which means the water doesn't wash into the sewer, along with oil, gas and pesticide residue. Called green pavement because of its environmental advantages, besides protecting our water supply, many green pavement products contain recycled materials.

Is green pavement actually green? Nope. Most permeable pavement is gray or beige in color, although some companies have developed a load-bearing grass turf that is strong enough even for a helicopter landing pad [source: Netlon]. Green pavement is a viable alternative for footpaths, driveways and parking lots, and one day it could revolutionize highway systems.

So, what's the difference between green pavement and asphalt or concrete? Read on to find out.

Advertisement