Shark Senses

One of the main reasons sharks are such effective predators is their keenly attuned senses. Initially, scientists thought of sharks as giant swimming noses. When researchers plugged the nasal openings in captive sharks, the sharks had trouble locating their prey. This seemed to demonstrate that the shark's other senses weren't as developed as the sense of smell. Further research demonstrated that sharks actually have several acute senses, but that they depend on all of them working together. When you take one away, it significantly hinders the shark's hunting ability.

The shark's nose is definitely one of its most impressive (and prominent) features. As the shark moves, water flows through two forward facing nostrils, positioned along the sides of the snout. The water enters the nasal passage and moves past folds of skin covered with sensory cells. In some sharks, these sensitive cells can detect even the slightest traces of blood in the water. A great white shark, for example, would be able to detect a single drop of blood in an Olympic-size pool. Most sharks can detect blood and animal odors from many miles away.

Advertisement

Another amazing thing about a shark's sense of smell is that it's directional. The twin nasal cavities act something like your two ears: Smell coming from the left of the shark will arrive at the left cavity just before it arrives at the right cavity. In this way, a shark can figure out where a smell is coming from and head in that direction.

Sharks also have a very acute sense of hearing. Research suggests they can hear low pitch sounds well below the range of human hearing. Sharks may track sounds over many miles, listening specifically for distress sounds from wounded prey.

In sharks, eyesight varies from species to species. Some less active sharks that stay near the water's surface don't have particularly acute eyesight, while sharks that stay at the bottom of the ocean have very large eyes that let them see in near darkness. Most all sharks have a fairly wide field of view, however, since their eyes are positioned on each side of the head. The most extreme example of this is the hammerhead, whose eyes actually protrude out from the head.

Many shark species also rely heavily on their sense of taste. Before these sharks eat something, they will give it a "test bite" first. The sensitive taste buds clustered in the mouth analyze the potential meal to see if it's palatable. Sharks will often reject prey that is outside their ordinary diet (such as human beings), after this first bite.

In addition to these familiar senses, sharks also possess some senses we don't fully understand.

The ampullae of Lorenzini give the shark electroreception. The ampullae consist of small clusters of electrically sensitive receptor cells positioned under the skin in the shark's head. These cells are connected to pores on the skin's surface via small jelly-filled tubes. Scientists still don't yet understand everything about these ampullary organs, but they do know the sensors let sharks "see" the weak electrical fields generated by living organisms. The range of electrosense seems to be fairly limited -- a few feet in front of the shark's nose -- but this is enough to seek out fish and other prey hiding on the ocean floor.

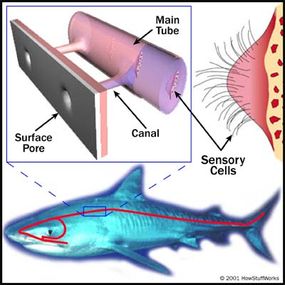

Another unique sense organ is the shark's lateral line. The lateral line is basically a set of tubes just under the shark's skin. The two main tubes run on both sides of the body, from the shark's head all the way to its tail. Water flows into these main tubes through pores on the skin's surface. The insides of the main tubes are lined with hair-like protrusions, which are connected to sensory cells. When something comes near the shark, the water running through the lateral line moves back and forth. This stimulates the sensory cells, alerting the shark to any potential prey or predators in the area.

By themselves, none of a shark's sense organs would be adequate for effective hunting. But the combination of all these senses make the shark an incomparable predator. The success of sharks is due largely to these physiological advancements -- they are superbly built to find food. They are also quite good at catching food, of course, as we'll see in the next section.