Bite-mark analysis is extremely complex, with many factors involved in a forensic dentist's ability to determine the identity of the perpetrator. It's also typically used in conjunction with other types of physical evidence.

When an investigator sees something on a victim that even resembles a bite, a forensic dentist is called in immediately, because bite marks change significantly over time. For example, if the victim is deceased, the skin may slip as the body decays, causing the bite to move.

The dentist first analyzes the bite to identify it as human. Animal teeth are very different from human teeth, so they leave very different bite-mark patterns. Next, the bite is swabbed for DNA, which may have been left in the saliva of the biter. The dentist also must determine whether the bite was self-inflicted.

Forensic dentists then take measurements of each individual bite mark and record it. They also require many photographs because of the changing nature of the bites. Bruising can appear four hours after a bite and disappear after 36 hours. If the victim is deceased, the dentist may have to wait until the lividity stage clears (the pooling of the blood), when details are visible. The bite photography must be conducted precisely, using rulers and other scales to accurately depict the orientation, depth and size of the bite. The photos are then magnified, enhanced and corrected for distortions.

Finally, bite marks on deceased victims are cut out from the skin in the morgue and preserved in a compound called formalin, which contains formaldehyde. Forensic dentists then make a silicone cast of the bite mark.

Forensic dentists use several different terms to describe the type of bite mark:

- Abrasion — a scrape on the skin

- Artifact — when a piece of the body, such as an ear lobe, is removed through biting

- Avulsion — a bite resulting in the removal of skin

- Contusion — a bruise

- Hemorrhage — a profusely bleeding bite

- Incision — a clean, neat wound

- Laceration — a puncture wound

Since several different types of impressions can be left by teeth, depending on the pressure applied by the biter, the forensic dentist notes these as well. A clear impression means that there was significant pressure; an obvious bite signifies medium pressure; and a noticeable impression means that the biter used violent pressure to bite down.

The movement of a person's jaw and tongue when they bite also contributes to the type of mark that is left. If the victim is moving while being bitten, the bite will look different from that inflicted on a still victim. And typically marks from either the upper or lower teeth are most visible, not both.

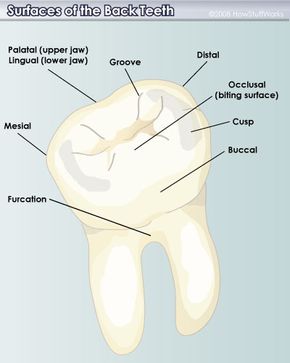

A forensic dentist can tell a lot about the teeth of the biter based on the bite mark, too. If there's a gap in the bite, the biter is probably missing a tooth. Crooked teeth leave crooked impressions, and chipped teeth leave jagged-looking impressions of varying depth. Braces and partials also leave distinctive impressions.

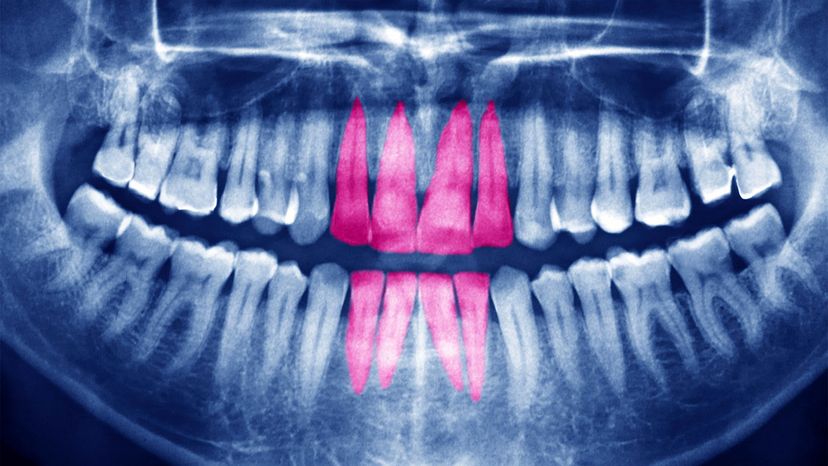

Once investigators have identified a suspect, they obtain a warrant to take a mold of their teeth, as well as photos of the mouth in various stages of opening and biting. They then compare transparencies of the mold with those of the bite-mark cast, and photos of both the bite mark and the suspect's teeth are compared to look for similarities.