Unless you're in a particularly remote area, you can't go far in most developed countries without finding a fast-food restaurant. You also can't go far without seeing cars, even if most of those cars are taxis. Much of the time, fast-food restaurants and cars seem to be everywhere. This is really no coincidence - without cars, we wouldn't have fast food.

The fast food phenomenon evolved from drive-in restaurants built in southern California in the early 1940s. Restaurateurs wanted to take advantage of the rising popularity of cars, so they designed restaurants that let people order and eat without leaving their vehicles. Drive-ins were busy and successful, but they generally used the same short-order style of food preparation that other restaurants did. The service wasn't speedy, and the food wasn't necessarily hot by the time a car hop delivered it.

Advertisement

Richard and Maurice McDonald owned such a restaurant. After running it successfully for 11 years, they decided to improve it. They wanted to make food faster, sell it cheaper and spend less time worrying about replacing cooks and car hops. The brothers closed the restaurant and redesigned its food-preparation area to work less like a restaurant and more like an automobile assembly line.

Their old drive-in had already made them rich, but the new restaurant - which became McDonald's - made the brothers famous. Restaurateurs traveled from all over the country to copy their system of fast food preparation, which they called the Speedee Service System. Without cars, Carl and Maurice would not have had a drive-in restaurant to tinker with. Without assembly lines, they would not have had a basis for their method of preparing food.

Before the McDonald brothers invented their fast-food production system, some restaurants did make food pretty quickly. These restaurants employed short-order cooks, who specialized in making food that didn't require a lot of preparation time. Being a short-order cook took skill and training, and good cooks were in high demand. The Speedee system, however, was completely different. Instead of using a skilled cook to make food quickly, it used lots of unskilled workers, each of whom did one small, specific step in the food-preparation process.

The McDonald brothers' changes also applied to the design of the restaurant kitchen. Instead of having lots of different equipment and stations for preparing a wide variety of food, the Speedee kitchen had:

- A very large grill where one person could cook lots of burgers simultaneously

- A dressing station where people added the same condiments to every burger

- A fryer where one person made french fries

- A soda fountain and milkshake machine for desserts and beverages

- A counter where customers placed and received their orders

Instead of being designed to facilitate the preparation of a variety of food relatively quickly, the kitchen's purpose was to make a very large amount of a very few items. For example, when Ray Kroc, who founded the McDonald's corporation, visited the restaurant for the first time in 1954, he was selling milkshake machines that could make five shakes at once. The McDonald brothers wanted eight of them.

Copies of the Speedee Service System spread throughout California and the rest of the United States as restaurateurs adapted the techniques for their own restaurants. Many of the chains that copied the McDonald brothers' ideas still exist - they serve everything from tacos to chicken. Even though they serve vastly different types of food, they have some basic traits in common:

- When you visit one of them and go inside, you almost always place your order and collect your food at a counter

- When you drive through, you place your order at a speaker or a window, and someone hands it to you through a window

- The food arrives individually wrapped and in a bag or on a tray

- You can eat most of the food without using a knife or fork

- The food is relatively inexpensive

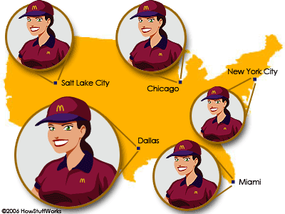

- Individual restaurants in the same chain physically resemble or are identical to one another

- When you visit different restaurants from the same chain, the menu and food are pretty much the same

There's one reason for this uniformity in fast food - it's a product of mass-production. We'll look a little more at the production of fast food next.