Imagine waking up in your bedroom with no idea of where you are. Something feels familiar about the cotton sheets, the pictures on the wall, the sheer curtains, but you can't place it. Minutes later, you feel that same sensation of waking up, but this time you're standing at your dresser, wearing a T-shirt and jeans with no recollection of ever having been in bed. It's as though your consciousness lacks a past and a future, like a stop-motion film in which every previous frame is destroyed.

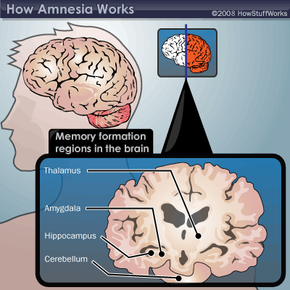

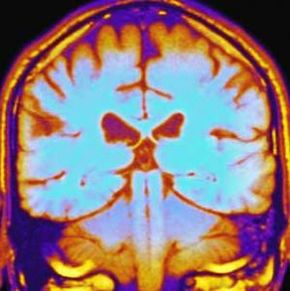

Clive Wearing lives in that perpetual present. The British musician and musicologist has the worst case of amnesia ever recorded [source: Sacks]. His memory span lasts a few seconds before it washes away in the blink of an eye and starts anew. Triggered by a case of herpes encephalitis, which infects the brain and causes it to swell, Wearing's amnesia has left him in a state of constant awakening in which every kiss, conversation or cup of coffee is his first.

Advertisement

The encephalitis eroded Wearing's ability to make new memories, severing any recollection of the recent past. According to a New Yorker profile on him, something as simple as eating an apple would seem almost like a magic trick in Wearing's mind. One moment, he holds a whole apple in his hand. The next, there's nothing left but the core.

Unlike most amnesia cases in which older memories are preserved, much of Wearing's long-term episodic memory of specific facts and events disappeared. His motor skills and general intelligence remain intact; it's the memory of using them that's disconnected. For instance, Wearing still plays the piano proficiently, but he wouldn't remember doing so, much less what song he played.

The nuances of his fragmented memory reflect the complexity of amnesia and the human brain. Wearing has always remembered his wife, Deborah, yet cannot immediately recall the name of his favorite composer, Lassus [source: Sacks]. In conversations about his life, Wearing can expound on some events; however, it is sometimes unclear whether his stories spring from true memories or his imagination [source: Sacks].

So how did amnesia erase Wearing's memory like a blackboard? And is having a perfect memory that great? Go to the next page to find out and to stroll down memory lane.