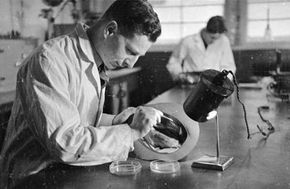

You've seen it on every crime drama on television: the gruff investigator breezes through the yellow police tape after flashing his badge, moving toward the scene of the grisly murder. He crouches down before the body; a few flashes coming from behind let us know photographs are being taken for documentation. While glancing over the body, carefully lifting pieces of clothing, nothing seems out of the ordinary -- just bruises and blood stains. But after a moment, he locks on the tiniest smudge near the victim's neck. In the following scenes, we'll see the investigator huddled over microscopes, computer screens and detailed documents, comparing samples and looking for matches.

Advertisement

When a crime is committed, police officers and investigators are left with mere fragments of a large and complex puzzle. In order to solve this puzzle, a network of trained specialists need to take into account several factors. These factors include time of death, location, temperature, trace evidence and any other clues that investigators are able to collect.

Television shows like "CSI: Crime Scene Investigation" make forensic science look driven by modern technology, with high power microscopes and computers doing lots of the work. However, the Chinese had successfully used fingerprinting to identify the origins of documents and clay sculptures as far back as the eighth century and could distinguish drowning from strangulation by the 13th century. But it wasn't until the late 19th century that scientists began seriously considering the importance of evidence at the scene of a crime, and rigorous standards for studying and analyzing criminal traces rapidly progressed during this era.

However, modern forensic science didn't just begin when microscopes became more powerful. Many ideas and philosophies about the nature of crime moved the study forward, and one of the most influential ideas in forensic science history is known as Locard's exchange principle.

What exactly is Locard's exchange principle? What does it have to do with forensic science? And who was Locard, the man behind the principle, anyway? Read the next page to find out how the simple yet groundbreaking idea behind Locard's exchange principle changed the way we fight crime.