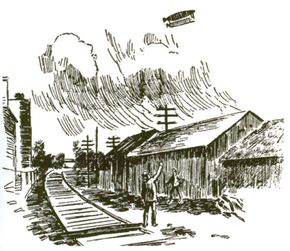

In the 19th century, accounts of UFOs took on a more believable tone.

As day dawned June 1, 1853, students at Burritt College in Tennessee noticed two luminous, unusual objects just to the north of the rising sun. One looked like a "small new moon," the other a "large star." The first one slowly grew smaller until it was no longer visible, but the second grew larger and assumed a globular shape. (Probably the objects were moving in a direct line to and from the witnesses or remaining stationary but altering their luminosity.) Professor A. C. Carnes, who interviewed the students and reported their sighting to Scientific American, wrote, "The first then became visible again, and increased rapidly in size, while the other diminished, and the two spots kept changing thus for about half an hour. There was considerable wind at the time, and light fleecy clouds passed by, showing the lights to be confined to one place."

Carnes speculated that "electricity" might be responsible for the phenomena. Scientific American believed this was "certainly" not the case; "possibly," the cause was "distant clouds of moisture." As explanations go, this was no more compelling than electricity. It would not be the last time a report and an explanation would make a poor match.

Unspectacular though it was, the event was certainly a UFO sighting, the type of sighting that could easily occur today. It represented a new phenomenon astronomers and lay observers were starting to notice with greater frequency in the Earth's atmosphere. And some of these sights were startling indeed.

On July 13, 1860, a pale blue light engulfed the city of Wilmington, Delaware. Residents looked up into the evening sky to see its source: a 200-foot-long something streaking along on a level course 100 feet above. Trailing behind it at 100-foot intervals cruised three "very red and glowing balls." A fourth abruptly joined the other three after shooting out from the rear of the main object, which was "giving off sparkles after the manner of a rocket." The lead object turned toward the southeast, passed over the Delaware River, and then headed straight east until lost from view. The incident -- reported in the Wilmington Tribune, July 30, 1860 -- lasted one minute.

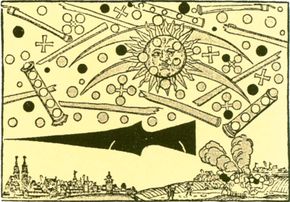

During the 1850s and 1860s in Nebraska, settlers viewed some rather unnerving phenomena. Were they luminous "serpents"? Apparently not, but instead elongated mechanical structures. A Nebraska folk ballad reported one such unusual sighting:

Twas on a dark night in '66 When we was layin' steel We seen a flyin' engine Without no wing or wheel It came a-roarin' in the sky With lights along the side And scales like a serpent's hide.

Something virtually identical was reported in a Chilean newspaper in April 1868 (and reprinted in Zoologist, July 1868). "On its body, elongated like a serpent," one of the alleged witnesses declared, "we could only see brilliant scales, which clashed together with a metallic sound as the strange animal turned its body in flight."

Lexicographer and linguist J.A.H. Murray was walking across the Oxford University campus on the evening of August 31, 1895, when he saw a:

brilliant luminous body which suddenly emerged over the tops of the trees before me on the left and moved east-ward across the sky above and in front of me. Its appearance was, at first glance, such as to suggest a brilliant meteor, considerably larger than Venus at her greatest brilliancy, but the slowness of the motion . . . made one doubt whether it was not some artificial firework. ... I watched for a second or two till [sic] it neared its culminating point and was about to be hidden from me by the lofty College building, on which I sprang over the corner . . . and was enabled to see it through the space between the old and new buildings of the College, as it continued its course toward the eastern horizon. . . . [I]t became rapidly dimmer . . . and finally disappeared behind a tree. . . . The fact that it so perceptibly grew fainter as it receded seems to imply that it had not a very great elevation. . . . [I]ts course was slower than [that of] any meteor I have ever seen.

Some 20 minutes later, two other observers saw the same or a similar phenomenon, which they viewed as it traversed a "quarter of the heavens" during a five-minute period.

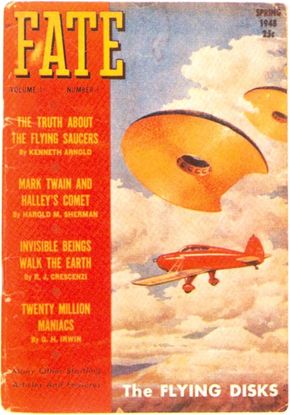

But in 1896 events turned up a notch: The world experienced its first great explosion of sightings of unidentified flying objects. The beginning of the UFO era can be dated from this year. Although sightings of UFOs had occurred in earlier decades, they were sporadic and apparently rare. Also, these earlier sightings did not come in the huge concentrations ("waves" in the lingo of ufologists, "flaps" to the U.S. Air Force) that characterize much of the UFO phenomenon between the 1890s and the 1990s.

Want to learn more about UFOs and aliens? Check out these articles: