Fish

Fish are an incredibly diverse group of animals. Read these articles to find out about all kinds of unique and different fish.

Learn More

At first glance, skate fish vs. stingray confusion is extremely understandable. Both belong to the class Chondrichthyes, the group of cartilaginous fish that includes sharks. They share flat bodies, wing-like pectoral fins, and bottom-dwelling habits.

By Nico Avelle

When it comes to salmon, not all fillets are created equal. The debate over sockeye vs. Atlantic salmon comes down to flavor, nutrition, habitat and how each fish is raised.

By Nico Avelle

They’re both long, sleek, and carry a sword-like bill, but when it comes to swordfish vs. marlin, these titans of the sea are anything but interchangeable. Whether you're into deep sea fishing or browsing seafood menus, knowing the difference between a swordfish and a marlin can make all the difference.

By Nico Avelle

Advertisement

With their serpentine bodies, massive jaws and slightly grumpy expressions, the wolf eel is one of the most misunderstood creatures beneath the waves.

By Nico Avelle

In the world of ocean giants, one name stands out: the Deep Blue shark.

By Nico Avelle

A summer day on the beach took a terrifying turn when a South Padre Island shark attack left beachgoers stunned and one woman seriously injured.

By Nico Avelle

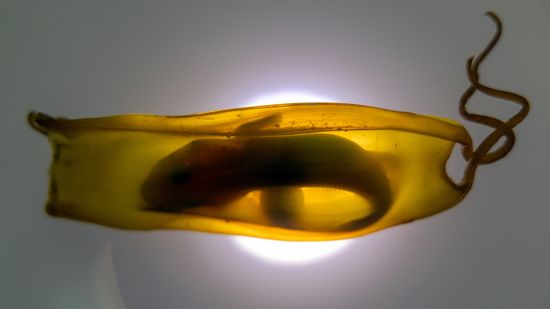

You’ve probably heard of shark attacks and shark teeth, but here’s something lesser known and just as intriguing: Do sharks lay eggs? The answer is: it depends on the shark species.

By Nico Avelle

Advertisement

Don’t let the name fool you: While it’s not a real shark, the rainbow shark definitely brings a bold, finned attitude to the freshwater aquarium.

By Nico Avelle

Forget the bloodthirsty predators of summer blockbusters; the ghost shark is a real and seriously mysterious. You sure won’t find them lurking off a sunny beach.

By Nico Avelle

Sleek, fast, and unmistakably tinted with ocean hues, the blue shark is a standout among pelagic sharks.

By Nico Avelle

With their sleek, spotted bodies and easygoing demeanor, the leopard shark is a California coast icon. These sharks, scientifically known as Triakis semifasciata, cruise the shallow nearshore embayments of the eastern Pacific, especially around San Francisco Bay and southern California.

By Nico Avelle

Advertisement

With a name that sounds like it belongs in a storybook, the tasselled wobbegong shark is one of the ocean’s most fascinating ambush predators.

By Nico Avelle

When you picture Belize — a Central American jewel hugged by the Caribbean Sea — your mind probably drifts to turquoise waters, coral reefs and epic scuba diving adventures.

By Nico Avelle

If the ocean had a drag race, the mako shark would leave the competition in its bubbly wake.

By Nico Avelle

When you think of Florida, you probably imagine sandy beaches, warm surf and maybe a dolphin or two gliding by. Or, you might be thinking about Florida shark attacks — which, while rare, tend to feed a few headlines every year.

By Zach Taras

Advertisement

If you’ve ever peered into a crevice while scuba diving and spotted something snakelike with a wide grin and sharp teeth, chances are you’ve encountered a moray eel.

By Nico Avelle

If you're into marine oddities, few animals capture the imagination quite like the hairy frogfish. This bizarre, underwater ambush predator may look like a ball of algae, but don't be fooled: It's a master of camouflage and a nightmare for unsuspecting prey.

The frilled shark (Chlamydoselachus anguineus), also known as the scaffold shark, is often called a "living fossil." This ancient shark has remained largely unchanged for millions of years, offering us a glimpse into the distant past. It's the only living species from its family of sharks.

By Mack Hayden

The barreleye fish (Macropinna microstoma) is known for its strange eyes and transparent dome for a head head — features that make it look more like a creature from science fiction than reality.

By Mack Hayden

Advertisement

The deep-sea dragonfish is one of the most mysterious and fearsome creatures lurking in the ocean's depths. Known as a top predator in the deep sea, this fish has evolved incredible adaptations to survive in underwater areas that have never known so much as a glimpse of sunlight.

By Mack Hayden

Fish may seem harmless compared to larger predators on land, but some of the deadliest animals are hiding in the oceans and rivers throughout the world. From venomous stings to sharp teeth, the most dangerous fish species can be lethal to humans.

By Mack Hayden

The stonefish might look like just another rock on the ocean floor, but don't let that fool you; it holds the title of the most venomous fish in the world. If you're not careful, a step on this camouflaged critter could lead to some serious consequences.

By Zach Taras

You've probably seen pufferfish on TV or at your local aquarium, puffing up like a balloon when they're startled. But there's way more to pufferfish than their signature defense mechanism. They're a diverse group of species with some truly unique traits.

By Zach Taras

Advertisement

Exploring the vast waters of our planet reveals some of the most awe-inspiring (or terrifying!) giants of the aquatic world. From the immense depths of the ocean to sprawling lakes and winding rivers, the largest fish represent the most enormous extant species in their habitats.

By Karina Ryan

Ever wondered what sharks might find in their waters besides fish? Turns out, some Brazilian sharpnose sharks (Rhizoprionodon lalandii) have been swimming in some rather strange seas - ones laced with cocaine.