Key Takeaways

- Weaponizing ticks as a delivery system for biological agents like Lyme disease is theoretically possible but highly impractical due to the ticks' preference for non-urban environments, slow feeding times, and the logistical challenges of infecting and dispersing them effectively.

- Lyme disease, caused by the Borrelia burgdorferi bacterium, wouldn't be an ideal bioweapon due to its low mortality rate, potential for long onset of serious illness, and the existence of other tickborne pathogens that can cause similar symptoms.

- Despite conspiracy theories, the focus should be on the real and ongoing issue of tickborne illnesses, with increased funding needed for research into their causes, diagnostics and treatments.

Ticks are vectors for all sorts of nasty germs, notably Lyme disease, the sixth-most commonly reported infectious disease in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Decades after it was first identified, it's still often misdiagnosed. Symptoms include an expanding body rash, joint pains, fatigue, chills and fever. Could the spread of Lyme be attributable to a classified, decades-old bioweapons program — as some people claim — or are ticks just as good for spreading misinformation as they are for germs?

The ticks-as-weapons issue made headlines back in July 2019, thanks to the U.S. House of Representatives' Chris Smith, R-N.J., who introduced legislation directing the Department of Defense to review claims that the Pentagon researched tick-based bioweapons in the mid-20th century. (The amendment passed.) Smith said he was inspired to do this by "a number of books and articles suggesting that significant research had been done at U.S. government facilities including Fort Detrick, Maryland and Plum Island, New York to turn ticks and other insects into bioweapons."

Advertisement

"With Lyme disease and other tick-borne diseases exploding in the United States — with an estimated 300,000 to 437,000 new cases diagnosed each year and 10-20 percent of all patients suffering from chronic Lyme disease — Americans have a right to know whether any of this is true," Smith said during a debate on the House floor. "And have these experiments caused Lyme disease and other tick-borne diseases to mutate and to spread?"

Congressman Smith's legislative actions were inspired partly by "Bitten: The Secret History of Lyme Disease and Biological Weapons," a book written by Kris Newby, a Stanford University science writer who also served as a senior producer on a Lyme disease documentary titled "Under Our Skin."

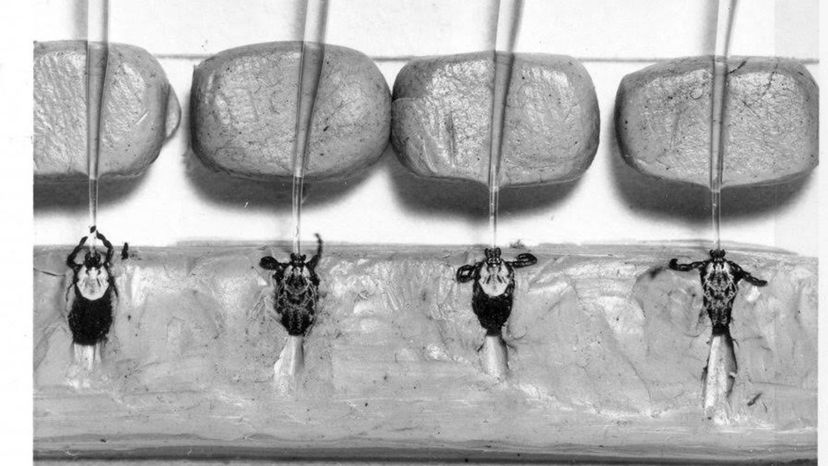

In the book, Newby points out that in 1953, the Biological Warfare Laboratories at Fort Detrick created a program investigating ways to spread anti-personnel agents via arthropods (insects, crustaceans, and arachnids), with the idea that slow-acting agents wouldn't immediately incapacitate soldiers, but rather make the area dangerous for a long period of time.

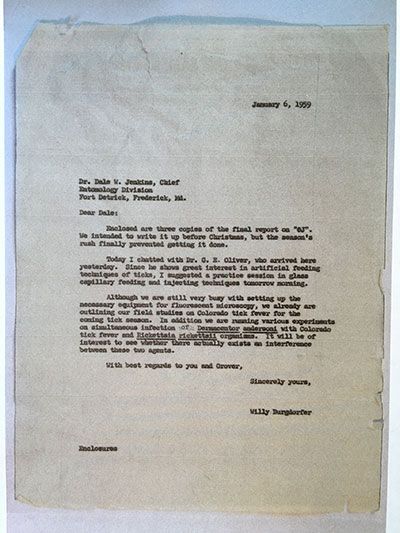

"The premise of my book is that weaponized ticks full of 'who knows what' were accidentally released in the region of Long Island Sound," says Newby by email. While she notes that she was unable to prove definitively Lyme bacteria was used as a bioweapon, "there are plenty of shocking discoveries and scientific leads to lift the veil on the mysteries surrounding tick diseases and the government's response to them." Her book says that scientist Willy Burgdorfer (who is credited with discovering the pathogen Borrelia burgdorferi that causes Lyme disease) was directly involved in a number of bioweapons programs. But she stops short of saying that his research was necessarily related to a Lyme disease weapon that was accidentally released into the wild.

Advertisement