Even though we can see a glowing object far in the distance, the human eye has its limitations, especially when it comes to visual acuity, the scientific-medical term for sharpness of vision.

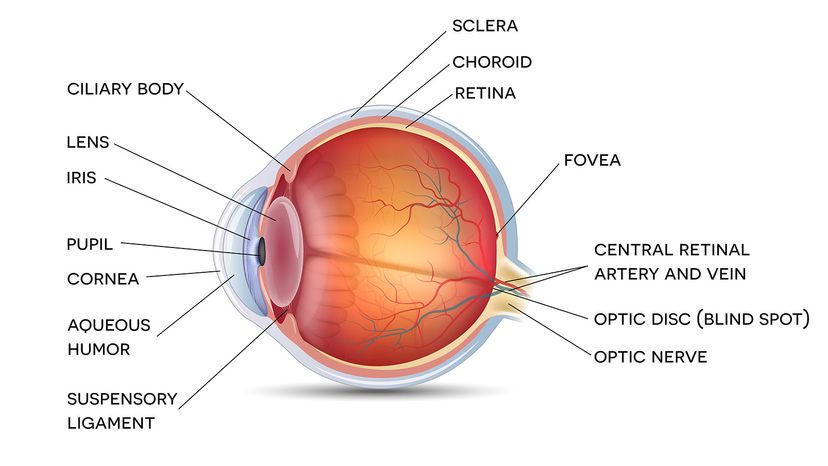

The cone cells — photoreceptors that are sensitive to red, green and blue wavelengths of light — are concentrated in the macula, an area in the middle of the retina. Our sharpest vision is at the center of the macula, in a spot called the fovea that can zero in on a small part of the world in front of you.

"You might think that you have a very wide visual field, but the reality is that your area of clearest vision is actually just a few degrees. You don't see the whole world clearly," Singman says. "If you take a big letter E, big as your hand, and move it about 15 to 20 degrees away to the side, you wouldn't be able to tell what letter it was. The clarity of your vision drops pretty quickly, once you get off the center."

That's the reason why macular degeneration, an eye condition in which the macula becomes damaged so that you lose that central vision, can be such a serious problem for people who get it. (The risk increases as you get older, according to the National Eye Institute.)

"You've got to remember that the brain is a really big part of this process," Singman says. That's evident in people who have some sort of brain injury that interferes with their vision, even if there's nothing wrong with their eyes.

"There are types of brain damage where you can't see something move, or where you can't recognize faces — you'll look and pick out an eye or a nose or mouth, instead of the whole face," Singman says.

The brain, in fact, can perform tricks to make up for the eyes' shortcomings. Singman recalls the case of a patient who after eye surgery, suddenly discovered that when he covered that eye, he couldn't see out of the other, supposedly good eye.

When a doctor examined the patient, it was discovered that he had a cataract, a natural clouding of the lens on that eye, but apparently had never noticed it because of his brain's ability to filter out the blur. "That's a classic trick — the brain can shut things off," Singman says.