Key Takeaways

- Abandoned mines pose safety and environmental risks due to potential collapses, toxic pollutants and groundwater contamination.

- These sites require careful monitoring to prevent harm to nearby communities and ecosystems.

- Proper management and rehabilitation of abandoned mines are essential in ensuring public safety and environmental protection.

What's the worst thing that could happen to you on a hiking trip? You trip over a rock and twist your ankle? You run into a grizzly bear? Or your friend falls into an abandoned vertical mine shaft? It may sound unbelievable, but about 30 people die each year in the United States from accidents involving abandoned mine operations [source: Geology]. These incidents are pretty devastating -- in 2006, a teenager visiting an abandoned mine fell 1,000 feet to his death during an attempt to jump over an exposed 10-foot-wide shaft [source: AP].

Throughout the world there are veritable fields of dangerous, exposed holes from mining operations that were simply abandoned after they stopped yielding minerals or coal. There are an estimated 100,000 to 500,000 abandoned mine sites in just the Western United States; the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) has identified and located 12,204 of those as of April 2008 [source: BLM].

Advertisement

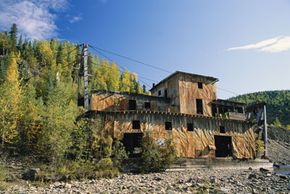

Startlingly, many of those abandoned mines yet to be identified aren’t on any map. And in some cases, there are no warning signs of the danger posed by the abandoned operations. Some of these mines were simply left to fall into disrepair and neglect. This is where that possibility of falling into a mine shaft on your hiking trip comes in.

What's more, abandoned mines could pose a danger to people who don’t even venture forth into the great outdoors. Mine tailings -- the remnants of materials left behind after the desired mineral is extracted -- are often simply piled on-site while a mine is in operation and left behind when the mine is abandoned. These tailings are often toxic, and when rain runs off the piles, it leaches out harmful toxins like lead, mercury and arsenic and caries them into nearby wetlands, threatening wildlife and exposing humans' drinking supplies to risk.

So who's responsible for cleaning up these mine sites, considering they pose such danger? Find out about programs created to address the problem of abandoned mines on the next page.

Advertisement