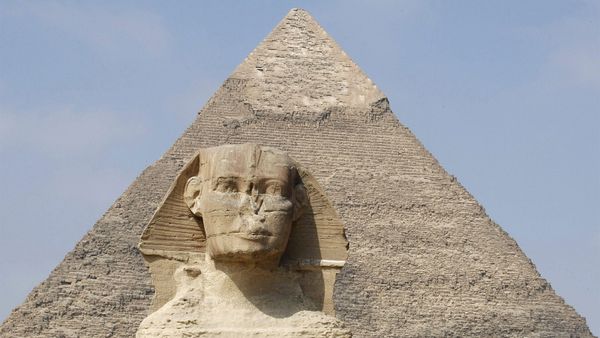

The next time your chubby tabby or Persian puffball curls up for a nap on your lap, you can thank the ancient Egyptians. DNA evidence suggests that wild cats first "self-domesticated" in the Near East and Egypt roughly 10,000 years ago when spotted felines wandered into early agricultural societies to feed on grain-stealing rodents and stuck around for the free scraps and backrubs from grateful humans.

But the level of devotion ancient Egyptians showed toward their cats went far beyond a pet owner's warm affection. Over the millennia, cats in Egypt evolved from useful village predators to physical embodiments of the gods and symbols of divine protection.

Advertisement

"The Egyptians looked at the cat the same way they looked at everything, as a way to explain and personify the universe," explains Egyptologist Melinda Hartwig, curator of ancient Egyptian, Nubian and Near Eastern art at Emory University's Michael C. Carlos Museum in Atlanta.

Hartwig wants to make one thing clear, though: Egyptians did not worship cats, but they did believe that cats held a bit of divine energy within them. The most widespread belief was that domestic cats carried the divine essence of Bastet (or Bast), the cat-headed goddess who represented fertility, domesticity, music, dance and pleasure.

For that reason, cats were to be protected and venerated. At the height of the popularity of the cult of Bastet, which took hold in the second-century B.C.E., the penalty for killing a cat, even by accident, was death. And charms and amulets depicting cats were worn by men and women to protect the home and bring good luck during childbirth. Jewelry fashioned into cats and kittens were popular New Year's gifts.

Most remarkable for modern archaeologists is the sheer number of mummified cats that have been recovered from burial sites across Egypt, including hundreds of thousands piled up in the catacombs of Saqqara and Tell-Basta, the chief worship sites for the goddess Bastet. At the Temple of Bastet in Tell-Basta, it's believed that priests maintained large "catteries" that supplied a thriving trade in cat mummies.

"Mummified cats would be sold to pilgrims who would go to the temple of the goddess Bastet and give the goddess back a little bit of her energy," says Hartwig. "They would also ask for a favor in the form of a prayer, known as a votive."

Hartwig says that so many cat mummies have survived the centuries because destroying them would have been prohibited in ancient Egypt, since they carried the essence of Bastet. So they wound up being stashed away in pre-existing burial chambers and secondary catacombs. An excavation this month in the pyramid complex at Saqqara unearthed dozens of cat mummies, including some buried in limestone coffins.

In the case of the coffins, Hartwig says those would have been reserved for family pets that died of natural causes. Other cats were undoubtedly killed and mummified to accompany their owners into the afterlife. And still more were temple cats and kittens sacrificed and mummified for the temple rituals.

Cats appear frequently in ancient Egyptian murals and artifacts, including the cast-bronze figurine of a cat nursing four kittens and a large limestone sculpture of a seated lion featured in a recent "Divine Felines" exhibit at the Carlos Museum. But most of the information we have about the Egyptians' veneration of cats comes via the ancient Greek historian Herodotus writing in the fourth-century B.C.E.

Hartwig isn't sure how much credence should be given to Herodotus' accounts, which go to great lengths to portray Egyptians as the exotic "other."

For example, according to Herodotus, Egyptian families would shave off their eyebrows if their pet cat died of natural causes and would shave off all body hair if their dog died. And if an Egyptian house caught on fire, Herodotus reported, the men wouldn't try to combat the fire, but focused all their attention on saving the cats and stopping them from leaping back into the blaze.

Herodotus also spread the colorful story of the Persian invasion of Egypt in 525 B.C.E., when the Persian King Cambyses II supposedly turned the Egyptians' love of cats against them in battle. Herodotus writes that Cambyses II had images of cats painted on his soldiers' shields and drove a large pack of cats and other pets ahead of his army. The Egyptians, so afraid of killing the animals and offending the goddess Bastet, surrendered.

Advertisement