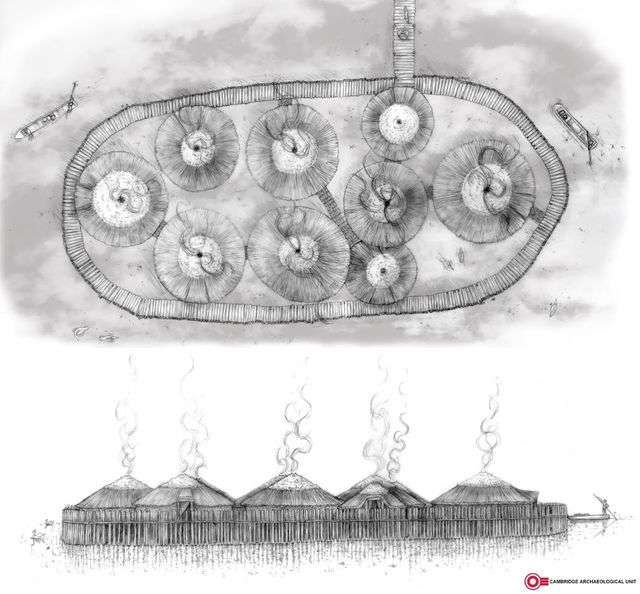

Three thousand years ago, a small Bronze Age settlement burned down in the Cambridgeshire Fens near modern day Cambridge, England. The village site now called Must Farm was built on stilts above a river, and during the fire, the structure supporting its nine or 10 roundhouses collapsed into the water, forcing the inhabitants to flee so abruptly they abandoned virtually everything — their jewelry, tools and clothes, the yarn they were spinning, the dinner they were cooking. All of it sank into the water and once the fire was extinguished, all evidence of these people's lives was buried in mud.

This event was objectively terrible for the 30 or so residents who called Must Farm home, but the product of this turn of events — the sudden fire, the collapse of the platform into the water, its envelopment in fine, non-porous sediment — is an archaeologist's dream scenario. Because everything was scorched and then sunk into anaerobic mud, the belongings of the Must Farmers show barely any decay, even after three millennia of sitting around in a bog. What we end up with is an almost perfectly preserved time capsule: a window into daily life in the late Bronze Age. Must Farm was so well preserved, in fact, that it's been referred to as Britain's own Pompeii.

Advertisement

Must Farm was discovered in 1999, when some of its wooden posts were noticed sticking up out of the site of a brick quarry. Serious scientific excavation of the site began in 2006, and in September of 2015, a final eight-month effort was launched to explore the structural remains of the settlement and the things on the timber platform that ended up in the river during the fire. This excavation has produced some of the most astounding finds in archaeological history: a bowl of vitrified grain with a spoon still sticking out of it, entire garments and pieces of cloth, and even intact balls of yarn.

"When excavating a Bronze Age site it's very unusual to find preserved fibres and fabrics," says Dr. Susanna Harris, an archaeology professor at the University of Glasgow, via email. "When they do turn up in Britain, they are usually fragments of textiles from a burial or cremation. At Must Farm this is different because the whole production processes is preserved in the houses of a settlement. There are bundles of fibre, evenly wound balls and bobbins of fine thread, as well as the finished fabrics."

Other treasures and artifacts have been found at Must Farm, most of which have been cataloged in the Must Farm Site Diary: metal weapons and household tools; distinctive pottery; a wheel that was indoors being repaired at the time of the fire; a delicate wooden box with the contents still inside; glass and amber beads; several longboats, some of them repaired with clay patches; and a lot of information about what the people living there ate, including the bones and even tracks of wild and domesticated animals in the nearby mud.

But the items that have provided archaeologists with the most new information about life in the Bronze Age are the plant-based textiles. Although no journal publications have yet come out of the Must Farm excavation, researchers have discovered the residents produced fabrics from at least two different plants: they grew flax to weave linen — some of the finest in Europe from that period — and also a fabric made from nettle and the inner bark of wild lime trees, which were foraged from the environment rather than cultivated.

"When the Must Farm village burnt down, plant fiber bundles were readied to be made into yarn and balls and bobbins of thread were being prepared to be woven into cloth," says Dr. Margarita Gleba, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research at the University of Cambridge. "One of the assumptions that most modern people have is that prehistoric cloth was like a coarse sack in quality, whereas the reality is that Bronze Age weavers produced fabric of astounding fineness. Some of the threads at Must Farm are about 0.1 mm in diameter — that is a thickness of a coarse human hair — and they were made by hand. I find uncovering these details both incredibly exciting and humbling."

Must Farm archaeologists have almost finished excavating the site, and soon they'll start the work of officially publishing their findings. Until then, you can stay up to date on what they're finding on the Must Farm Facebook page.

Advertisement