Another prolific American inventor, Oliver Evans, would take the principles developed by Franklin and Hadley and draw up a design for a vapor-compression cycle, or early refrigerator, in 1805.

Evans' first love, however, was the steam engine, so he set his plans on ice while he spent his energy developing things like a steam-powered river dredger. Thankfully, however, Evans' design didn't go to waste.

While in Philadelphia, Evans became friends with a young inventor called Jacob Perkins. Even as a teenager, Perkins displayed remarkable ingenuity, inventing a way to plate shoe buckles at the age of 15.

The precocious inventor saw the promise in Evans' work on refrigeration, and he took Evans' design and began modifying it, receiving a patent on his own design — called a compression refrigeration cycle — in 1834 [source: The Heritage Group]. This cycle formed the basis for modern refrigeration systems and air conditioning.

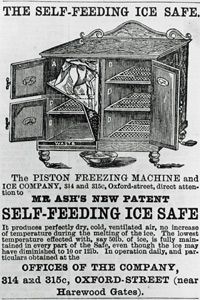

Perkins then persuaded a man named John Hague to construct the first practical refrigeration machine, which utilized a closed-cycle system that involved the compression and expansion of a volatile fluid (often ether or other gases) to create cooling effects.

Let There Be Ice

Created more as an experiment than something fit for commercialization, Perkins' product certainly had room for improvement. For instance, since Freon wouldn't be invented for another century or so, early refrigerators like Perkins' used potentially dangerous substances such as ether and ammonia to function.

Still, his device did manage to produce a small quantity of ice by drawing on the same fundamental principles used in the modern refrigerator.

Following the young inventor's success in creating a functioning fridge, other inventors moved the device rapidly toward commercialization. As for Perkins, he retired soon after inventing the refrigerator and died in 1849, never witnessing the tremendous impact his invention had on modern life and mechanical refrigeration systems [source: Heritage Group].