To understand viruses, it may help to consider the French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. In the early 19th century, Bonaparte invaded much of Europe in order to establish French dominance over the continent. He's also known for being somewhat short in stature (however unfair that reputation may be).

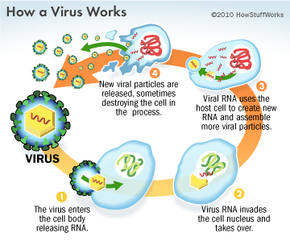

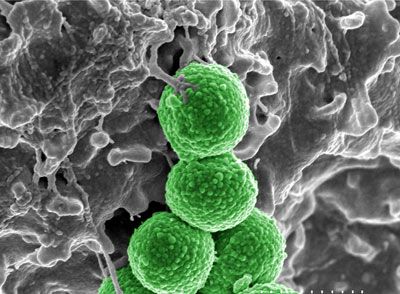

Like our idea of Napoleon, viruses are very small -- 100 times smaller than the average bacterium, so small that they can't be seen with an ordinary microscope. Viruses can only exert influence by invading a cell, because they're not cellular structures. They lack the ability to replicate on their own, so viruses are merely tiny packets of DNA or RNA genes enfolded in a protein coating, on the hunt for a cell they can dominate.

Advertisement

Viruses can infect every living thing -- from plants and animals down to the smallest bacterium. For this reason, they always have the potential to be dangerous to human life. Still, they don't become truly treacherous until they infect a cell within the body. This infection can happen several ways: by air (thanks to coughing and sneezing), via carrier insects like mosquitoes, or by transmission of body fluids such as saliva, blood or semen.

Once a virus infects a cell, it tries to take over its host completely, much as Napoleon spread the French influence with every country he fought. A virus lodged in a cell replicates and reproduces as much as possible; with each new replication, the host cell produces more viral material than it does normal genetic material. Left unchecked, the virus will cause the death of the host cell. Viruses will also spread to nearby cells and begin the process again.

The human body does have some natural defenses against a virus. A cell can initiate RNA interference when it detects viral infection, which works by decreasing the influence of the virus's genetic material in relation to the cell's usual material. The immune system also kicks into gear when it identifies a virus by producing antibodies that bind to the virus and render it unable to replicate. The immune system also releases T-cells, which work to kill the virus. Antibiotics have no effect on viruses, though vaccinations will provide immunity.

Unfortunately for humans, some viral infections outpace the immune system. Viruses can evolve much more quickly than the immune system can, which gives them a leg up in uninterrupted reproduction. And some viruses, such as HIV, work essentially by tricking the immune system. Viruses cause many diseases, including colds, measles, chicken pox, HPV, herpes, rabies, SARS and the flu. Though they're small, they pack a big punch -- and they can only sometimes be sent into exile.

Advertisement