We're all familiar with the basics of viruses: These particles infect living cells and basically wreak havoc throughout the body. But viruses aren't the only villains around causing chaos in living things. Other infectious agents called viroids and prions — which are also tiny but powerful — can take down both plant life and entire animals.

How are viroids and prions the same as viruses? And how are they different? All three — viruses, viroids, and prions — are acellular particles. Acellular particles are not alive, which means:

Advertisement

- They're not made of cells.

- They don't transform energy.

- They can't reproduce on their own.

- They can only be seen with an electron microscope.

- They don't grow or divide.

Acellular particles can hang around forever — sitting on a countertop or on a doorknob, doing nothing and causing no harm. However, viruses, viroids and prions are infectious agents. Once they enter a suitable cell, be it animal, plant or bacterial, they take over the cell's metabolic agents to increase their own numbers [source: Paustian].

You can almost think of them as hijackers. The only goal for viruses, viroids and prions is reproduction, and the only way for them to achieve that goal is to take over host cells. Once they take over, they use those cells to alter normal functioning and make new virus particles. These particles can cause disease in plants, animals and humans — and they've even changed the history of life on Earth by changing the DNA of various organisms.

Now let's look at how the three are different, starting with viruses.

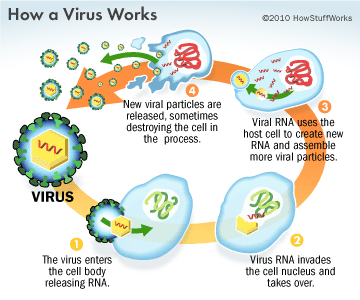

A virus is a package of genetic material. This genetic material is either deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) or ribonucleic acid (RNA). This little package is carried in a shell called the capsid. Some viruses have an extra envelope covering the capsid. While covered in its capsid, a virus is in an extracellular state. This means the virus hasn't invaded a host cell and is pretty much just hanging around doing nothing.

However, once a virus invades a host cell, it becomes intracellular, and that's when the action starts. A virus can infect a cell several different ways — through bodily fluids (such as saliva or blood), air (sneezing or coughing) or a mosquito bite. The virus then begins its attack by triggering the cell to let it in and take control. The virus starts replicating and overriding the cell's normal functioning and, in some cases, inserts its own genetic material into the cell's DNA. The cell actually does all the work — the virus just calls the shots. The virus becomes a commander and starts sending out more infectious troops into the body.

Even though the body has natural defenses against viruses, many viral infections replicate so rapidly that our immune system simply can't keep up. Antibiotics are useless against viruses, although immunizations work. Common examples of viruses include:

- Chicken pox

- HIV

- Common cold

- Measles

- Rabies

- Herpes

- West Nile Virus

So how do viroids and prions operate differently?

Advertisement