A straitjacketed patient rocks back and forth in a dank "insane asylum" on TV. A bloodied actor in a straitjacket stalks his victims in a haunted house attraction. In popular culture, straitjackets are code for "crazy scary."

In real life, straitjackets appear far less often — and very rarely, if ever, in psychiatric hospitals. Largely considered an outmoded form of restraint for people with mental illness, they've been replaced with other physical means to prevent patients from injuring themselves or others.

Advertisement

And that's when physical restraints are even used at all. Mental health facilities have better tools now — medication, nonconfrontational techniques, higher staffing levels — to keep patients safe, says Dr. Steven K. Hoge, a professor at Columbia University Medical School and chairman of the American Psychiatric Association's Council on Psychiatry and the Law.

Facilities and doctors operate under a different ethos now, as well, Hoge says. Restraints are viewed as an infringement on a patient's liberties, which mental health care providers are more concerned with these days than they were in, say, 1975, when Jack Nicholson's character was strapped down for electroconvulsive therapy (in an adaptation of 1962's "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest").

In almost 35 years of practice, including at the maximum-security mental health unit at Bellevue Hospital in New York City, Hoge has never seen or heard of a straitjacket being used to restrain a patient.

"This is like leeches," he says. "It would be something worthy of comment."

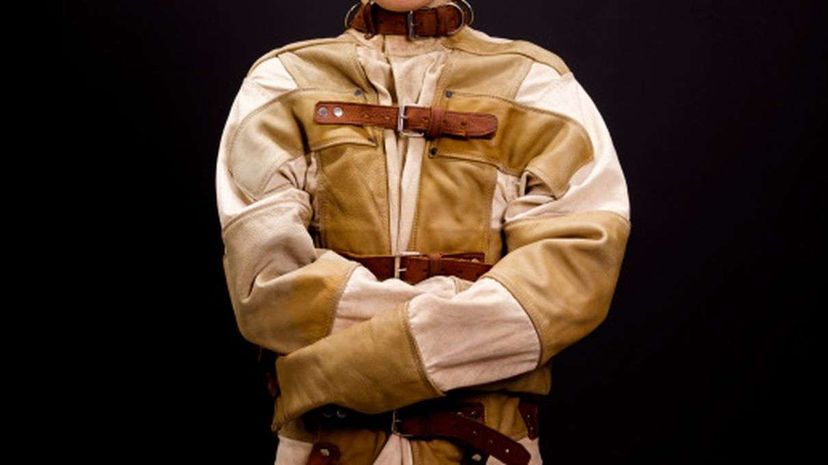

So why the enduring popular interest in straitjackets? There's something provocative about them. Just the idea of being wrapped up in one — arms folded across midsection, sleeves secured in back — might prompt even mild claustrophobics to spread their arms and shake them out.

And, although straitjacket sales are low, people still make them, and people still use them: on an Ohio man with Alzheimer's disease; on an 8-year-old with autism in Tennessee; on a prisoner in a county jail in Kentucky.

But, for one company that makes them, it's a small market.

"You're talking less than 100 units a year," says Stacy Schultz, general manager of Humane Restraint, of Waunakee, Wisconsin. The company also sells ankle and wrist restraints, transport hoods and "suicide smocks" — garments designed so the wearer can't tear or roll them.

The straitjackets mostly go to "custodial folks," Schultz says — jails and prisons.

And that's probably where, if you were going to find a straitjacket in use, it would be, says Hoge, the psychiatrist. Jails and prisons — called America's "new asylums" in 2014 by the Treatment Advocacy Center, housing 10 times more seriously mentally ill people than state psychiatric hospitals — lack mental health resources and staffing, Hoge says, and typically don't follow hospital standards.

"You see all sorts of things in prisons that you don't see in ordinary mental hospitals," he says.

The American Bar Association seems to have taken note. Its Standards on Treatment of Prisoners, approved in 2010, says correctional facilities should not use physical restraints to punish prisoners.

Among its list of mechanical devices deemed not OK for meting out punishment: leg irons, handcuffs, spit masks — and straitjackets.

Advertisement