The essential idea has been the subject of scientific and science fictional cosmology for decades, but MIT radio astronomer John Ball is often credited with laying out the hypothesis in 1973. In essence, the zoo hypothesis serves as a possible solution to the Fermi paradox.

Named for physicist Enrico Fermi, the Fermi paradox refers to the contradiction between the high likelihood of system-spanning intelligent life (according to some interpretations of the Drake Equation, which is used to estimate the number of communicating civilizations in our galaxy) and the lack of evidence for such intelligent life. The aliens might be there, the hypothesis suggests, and they might be intentionally hiding from us.

As the name implies, one way to imagine such a scenario is that Earth could be set aside as a sort of zoo or nature reserve. Perhaps the aliens just prefer to observe life in a closed system, or they could have ethical reasons for not interfering in our technological and cultural progress — akin to the Prime Directive from TV's "Star Trek." A potentially more sinister interpretation can be found in Ball's laboratory hypothesis: The aliens don't talk to us because we're part of an experiment they're conducting.

As astrophysicists William I. Newman and Carl Sagan explained in their 1978 paper "Galactic Civilizations: Population Dynamics and Interstellar Diffusion," it's ultimately impossible to predict aims and beliefs of a hypothetical advanced civilization. However, they stressed that such ideas are worthwhile in that they help us imagine "less apparent, social impediments to extensive interstellar colonization."

In other words, if we're putting all ideas on the table concerning the possibility of advanced alien life, then the zoo hypothesis has a place in the cosmological Lazy Susan. But as particle physicist and co-author of "Frequently Asked Questions About the Universe" Daniel Whiteson points out, we have to be careful about avoiding anthropocentrism, the tendency to assume that human beings are at the center of cosmic concerns.

"I think that's pretty unlikely," Whiteson tells us. "I don't like that it [the zoo hypothesis] puts us at the center of things. And it also just seems implausible because it requires a vast galactic conspiracy. When was the last time anybody worked together to keep a secret? The best argument against having secret aliens visiting the earth is just that governments are not capable of maintaining secrecy like that, especially over decades."

You might be tempted to argue that, well, we're talking about alien governments here and not human governments. But our contemplation of possible alien life is largely based on the only existing model we have: us. If we can't maintain vast conspiracies, then what chance do aliens have?

"I think it's very unlikely that aliens are somehow capable of that, though perhaps they are," Whiteson admits. "I like that it [the zoo hypothesis] tries to answer this question in a whimsical, creative way. It's fun for telling a story, but it puts a lot of human motivations in the minds of these unknown aliens."

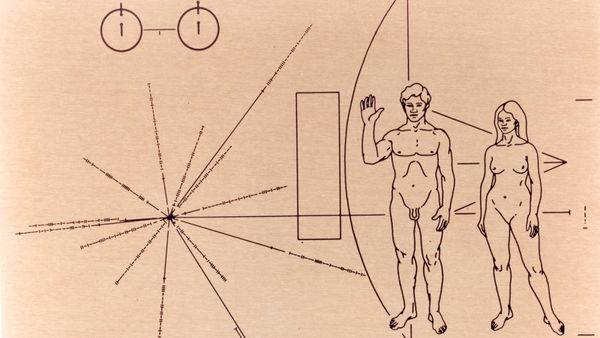

But as Newman and Sagan pointed out, the idea isn't entirely untestable. If we could one day detect alien communications, the zoo hypothesis would be falsifiable. The nonprofit group Messaging Extraterrestrial Intelligence (METI) advocates the creation and transmission of interstellar messages that could, in theory, let any cosmic zookeepers out there know that we would like to see beyond our enclosure.