Key Takeaways

- Trinitite is a green, glassy substance formed from the sand at the Trinity Site in New Mexico during the world's first atomic bomb test.

- Initially believed to have formed from sand melting at ground level, a 2010 study revealed trinitite sand was actually pulled into the explosion, melted at high temperatures, and then cooled and solidified as it fell.

- Although it's now illegal to remove trinitite from the blast site, it can still be bought and sold if previously collected.

It was theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer who chose the codename "Trinity," though he could never remember why. As a participant in the Manhattan Project, he oversaw the construction of four atomic bombs. By the spring of 1945, the U.S. military had started looking for a place to test one of them out. Sites in California, Colorado and Texas were considered before the Pentagon chose a patch of terrain at the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico.

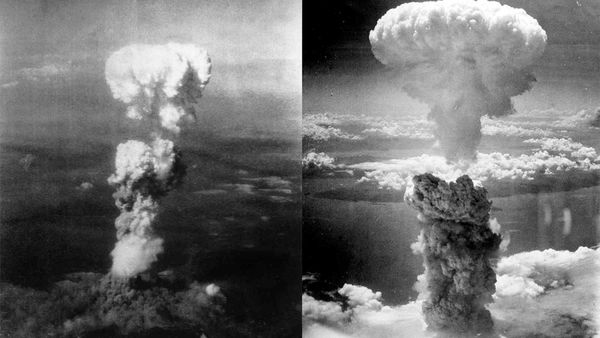

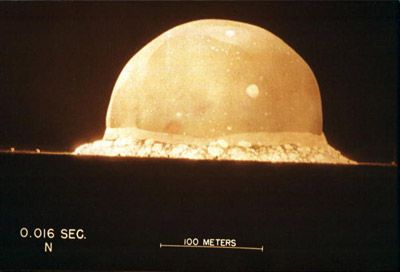

For reasons he'd come to forget, Oppenheimer codenamed this historic trial run "The Trinity Project." On July 16, 1945, at 5:29 a.m. Mountain Time, a plutonium bomb — known simply as "The Gadget" — was detonated at the site. This marked the first deployment of an atomic weapon in recorded history. Within a month, the United States used two atomic bombs to level both Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan and help bring World War II to an end. So began the Atomic Age.

Advertisement

Back in New Mexico, scientists discovered that the explosion that started it all had left something behind. Nuclear physicist Herbert L. Anderson and his driver inspected the Trinity blast site shortly after the bomb detonated. Over the radio, he announced that the area had turned "all green." A layer of small, glassy beads covered the crater. Most were olive green in color — though some samples were black or reddish in hue. The substance is now known as "trinitite."

Plenty of trinitite was still there in September 1945, when a Time magazine report described the crater as "a lake of green jade shaped like a splashy star." Physicists realized that this trinitite was desert sand that melted down during the blast and then re-solidified.

Our understanding of trinitite has changed recently. At first, scientists assumed that the grains of sand that turned into this material had melted at ground level. But a 2010 study found that the sand was actually pulled up into the heart of the explosion, where high temperatures liquified it. The stuff later rained down, cooled and turned solid.

There are no laws against buying or selling trinitite samples that've already been collected, but it's now illegal to remove this substance from the blast field. You won't find much of it in situ anyway: America's Atomic Energy Commission bulldozed over the nuclear test site in 1953. In the process, a bounty of trinitite was buried underground. And there's a lot of phony trinitite on the market.

These kinds of glassy residues are left behind wherever nuclear weapons go off at ground level; they've been recovered in the wake of atomic tests over such places as the Algerian Desert. That being said, the name "trinitite" is typically reserved for specimens from the original Trinity Site at White Sands Missile Range. Some scientists prefer to call material found in other parts of the world "atomsite." Russian nuclear tests gave rise to an analogous substance called "Kharitonchiki." Named after weapon designer Yuly Khariton, these porous black blobs were created from fused rock.

Advertisement