On July 5, 1996, the most famous sheep in modern history was born. Ian Wilmut and a group of Scottish scientists announced that they had successfully cloned a sheep named Dolly.

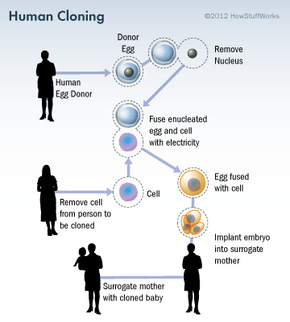

If you stood Dolly beside a "naturally" conceived sheep, you wouldn't notice any differences between the two. In fact, to pinpoint the only major distinguishing factor between the two, you'd have to go back to the time of conception because Dolly's embryo developed without the presence of sperm. Instead, Dolly began as a cell from another sheep that was fused via electricity with a donor egg. Just one sheep -- no hanky-panky involved.

Advertisement

While Dolly's birth marked an incredible scientific breakthrough, it also set off questions in the scientific and global community about what -- or who -- might be next to be "duplicated." Cloning sheep and other nonhuman animals seemed more ethically benign to some than potentially cloning people. In response to such concerns in the United States, President Clinton signed a five-year moratorium on federal funding for human cloning the same year of Dolly's arrival [source: Lamb].

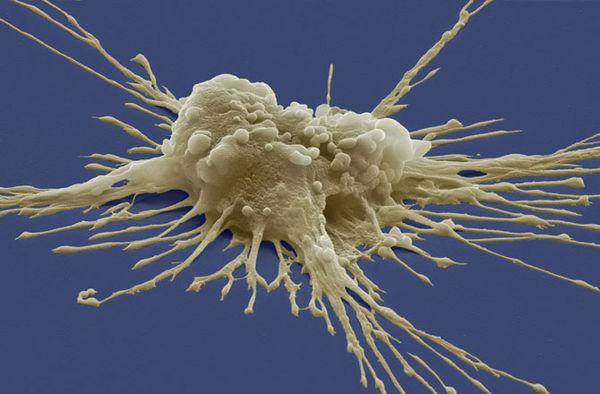

Today, after more than a decade since Dolly, human cloning remains in its infancy. Although cloning technology has improved, the process still has a slim success rate of 1 to 4 percent [source: Burton]. That being said, science is headed in that direction -- pending governmental restraints.

Scientists have cloned a variety of animals, including mice, sheep, pigs, cows and dogs. In 2006, scientists cloned the first primate embryos of a rhesus monkey. Then, in early 2008, the FDA officially deemed milk and meat products from cloned animals and their offspring safe to eat.

But what would human cloning involve, and how could you take sperm out of the reproductive equation?

Advertisement