Who was Edmond Locard?

In 1887 -- when Sir Arthur Conan Doyle published "A Study in Scarlet," the first story featuring iconic English detective Sherlock Holmes -- scientists were attempting to separate fact from fantasy at the crime scene. Despite the fictional world of Dr. Holmes, Doyle's stories were a major influence on forensic science and, as we'll see, Edmond Locard himself. Previously, evidence took a backseat to witness testimonies, the latter of which could often be dubious. In England, for instance, superstition, squeamishness and emotional respect toward a dead victim prevented investigators from performing invasive procedures like incisions, thereby limiting the amount of data they could collect.

By the turn of the century, however, rapid advances in areas of study such as microscopy and anatomy strongly introduced science into the process of criminal investigation. The necessity to pay strict attention to the physical details at a crime scene and meticulously record observations became habit.

Advertisement

Alphonse Bertillon, a French criminal investigator, developed one of the earliest systems of documenting personal evidence on criminals in the late 19th century. Called Bertillonage, the procedure was a relatively simple way of recording physical measurements onto identification cards and then filing them in order along with photographs of the individual. Although basic when compared to fingerprinting and today's computer systems, Bertillonage was an effective way of keeping precise information on criminals and acknowledging the importance of physical evidence.

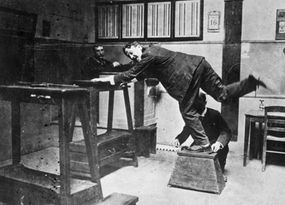

One of the most important figures in the history of forensic science was a student of Bertillon, Edmond Locard, who would carry many of his teacher's influences with him. Locard worked as a medical examiner during World War I and was able to identify causes and locations of death by looking at stains or dirt left on soldier's uniforms, and in 1910, he opened the world's first crime investigation lab in Lyons, France. Like Doyle's Holmes, he was somewhat of an Everyman, and he worked with great faith in analytical thought, objectivity, logic and scientific fact.

Locard also wrote a highly influential seven-volume work on forensic science, titled "Traité de criminalistique," and in it and his other works as a forensic scientist, he developed what would become known as Locard's exchange principle. In its simplest form, the principle is known by the phrase "with contact between two items, there will be an exchange."

Sounds easy enough, but how does it relate to a crime scene? To learn what Locard's exchange principle means, read the next page.