When a person dies violently or unusually, or in an untimely fashion, difficult questions invariably follow.

What happened? Could it have been prevented? Is foul play involved? Has a crime been committed? Should we be worried?

Advertisement

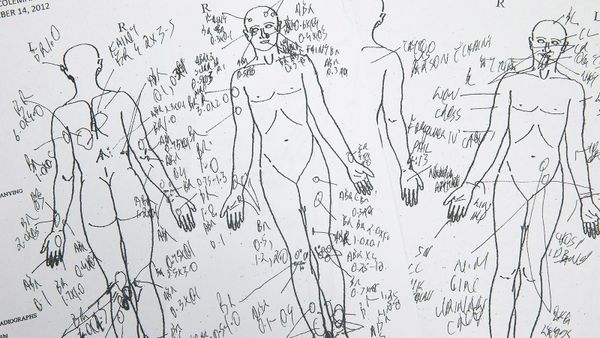

Those are the questions that coroners, medical examiners and forensic pathologists wrangle with every day. They are the ones that have to find answers for the living.

"Morally, I think we can be judged as a civilization on how we treat those that are dead," says Gary Watts, the coroner in Richland County, South Carolina. "We talk about it all the time. I don't care if we're dealing with somebody that was found under a bridge or was found in a $5 million house. We're going to treat 'em with respect and dignity. We're going to take care of their families."

In carrying out their duties, though, many of America's death investigators — mostly medical examiners and coroners, whose work is supported by taxpayers — are hampered by a lack of manpower, chronic underfunding and a general coolness toward their work.

Whether people want to face it or not, though, these real-life Quincys are critically important. Death investigators not only uncover possible foul play, but they can spot infectious diseases and are among the first to identify epidemics and other public health concerns.

Advertisement