Mood-altering drugs often go in and out of favor. In the 1960s, psychedelic drugs were all the rage, as the counterculture glorified the use of marijuana and LSD as part of rebellion against mainstream norms. But by the end of the 1970s, cocaine was the popular drug — so popular and so cheap — that dealers weren't making the kind of money that they used to. So some of them came up with a clever profit-making solution, converting cocaine powder into smaller chunks that could be smoked. Smoking these chunks created a more euphoric effect with a much shorter-lived high than snorting cocaine. The new drug was called crack cocaine (crack), a powerful mind-altering substance that comes loaded with a sinister mystique and a reputation for ravaging individual lives and entire neighborhoods [source: Drug Free World].

In the 1980s, the so-called crack epidemic gripped America, garnering frantic headlines around the country and the Western world. Sordid tales of instantaneous addiction, spikes in violent crime, and lives shattered were the topic of newspapers and TV programs for years. Stories of "crack babies," "crack prostitutes" and "crack-addicted criminals" filled the airwaves. Nearly 6 million citizens admitted to using cocaine and its crack derivative in the mid-'80s. The scourge spread to other areas of the Americas, Europe, and beyond.

Advertisement

Government officials and social workers decried the epidemic as rending communities into pieces. Whites made up the bulk of crack users, but blacks comprised the vast majority of arrests and prosecutions. The 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that 55 percent of past-month crack users were white and 37 percent were black. But blacks were 21.2 times more likely than whites to go to federal prison on a crack charge — indeed, 80 percent of the people in federal prison on crack charges are black [sources: Drug Policy Alliance, Criminal Justice Police Foundation].

Fortunately, in the United States, crack usage is steadily declining. Fewer than 5 percent of Americans aged 18-25 between 2002 and 2010 have ever tried the substance. Even so, there are still many suffering in the throes of major addiction, often because crack is a cheap and easy way to self-medicate the effects of extreme poverty and trauma or to feed a genetic predisposition for addiction [source: Criminal Justice Police Foundation].

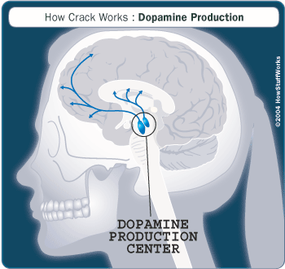

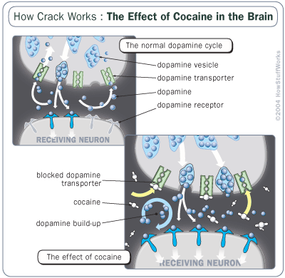

Even as crack usage slides, its chemistry, distribution, and reputation continue to affect individuals, families, and nations around the world. But what is crack, exactly? How is it made, and how does it alter the brain's functions to create addiction?