Some of the most momentous occasions in the life of Queen Elizabeth II – her 1947 marriage to Philip Mountbatten, and her 1953 coronation – took place in Westminster Abbey. On Sept. 19, 2022, her state funeral will be held there too, marking the end of a 96-year life and a seven-decade reign as the United Kingdom's monarch. Westminster Abbey has been the backdrop for important royal events for more than 1,000 years. Here are five fascinating things you might not know about the iconic World Heritage Site.

Advertisement

1. Westminster Abbey Is Not Actually an Abbey at All

The word "abbey" refers to a building used by monks or nuns; neither live at Westminster Abbey today. But the name is a holdover from the building's earliest days, explains Dr. John Cooper, director of the Society of Antiquaries of London, in an email interview. "Westminster Abbey was founded as a monastery of Benedictine monks around the year 960, a century before Anglo-Saxon England was conquered by the Normans," he says. "Benedictine monks wore black habits and were devoted to a simple life of poverty, chastity and obedience. But as the Palace of Westminster became the center of English royal government and ceremony, so the Abbey became the place where coronations and many royal burials were held."

During the Reformation, King Henry VIII dissolved all the English monasteries. The Abbey is now something known as a "royal peculiar," because it technically belongs not to the Church of England, but directly to the monarchy. "The two most famous examples [of royal peculiars] are Westminster Abbey, where Queen Elizabeth II's funeral service will be held, and St. George's Chapel at Windsor, where she will be laid to rest with her late husband the Duke of Edinburgh in a private service," says Cooper.

Perhaps most surprising: Westminster Abbey isn't actually the building's name anymore. "Formally," Cooper says, "it is the 'Collegiate Church of St. Peter, Westminster,' but almost everyone calls it by its historic name of Westminster Abbey."

Advertisement

2. There's Not Much of the Original Abbey Left

While Westminster Abbey was originally dedicated in 1065 C.E., under the reign of King Edward the Confessor, most of that original building was demolished in the 13th century when Henry III rebuilt the church. "The earliest Abbey buildings survive only as archaeological traces," says Cooper. "But much of Henry III's Gothic Abbey of the thirteenth century can still be seen today, including the Chapter House with its tiled floor, the Purbeck marble shrine of St. Edward the Confessor, and wall-paintings of St. Christopher and Doubting Thomas that were rediscovered in the 1930s."

And while the two iconic towers on the front of Westminster Abbey might look medieval, they're actually the youngest part of the building, designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor and completed in the 1740s.

Advertisement

3. It's Loaded With Bodies

There are more than 3,000 people buried in Westminster Abbey, so most visitors can't help but walk over a lot of graves. But some tombs are more notable than others.

For centuries, the Abbey was the final resting place of England's kings and queens; 30 of them, to be exact. The royal tombs are some of the most well-known spots in the church. "As a Tudor historian, my favorite place in the Abbey has to be the Henry VII Chapel in the east end," says Cooper. "As a king who had won the throne by conquest, Henry VII was obsessive about displaying his legitimacy to rule. By creating a magnificent new royal mausoleum in Westminster Abbey, he ensured that he and his successors would be remembered in perpetuity in England's greatest church."

The last monarch to be buried there was George II, but sometime in the mid-1600s, a practice began of burying nonroyals in Westminster Abbey. Of course, it was an honor not bestowed on just anyone: These graves are a veritable who's who of English literature, science and culture, including Geoffrey Chaucer, William Shakespeare and more than 100 other poets and writers, the scientist Sir Isaac Newton, Prime Ministers Pitt the Elder and Pitt the Younger, and the naturalist Charles Darwin. The most recent burial at Westminster was for physicist Stephen Hawking, whose ashes were interred near Newton's in 2018.

Advertisement

4. It Houses the Most Famous Chair in the World

The Coronation Chair is one of the most famous pieces of furniture in the world. It was originally commissioned in 1300 by King Edward I to hold the massive Stone of Scone, which Edward had taken from Scotland. Also known at the Stone of Destiny, the huge block of sandstone is where Scottish kings were crowned beginning in about the year 498. Once it was placed under the care of the Abbot of Westminster, the coronation chair – a large throne made of oak – was built to sit atop it.

The Coronation Chair was painted with colorful plants, animals and birds, all highlighted with gold gilt. There have been 38 coronation ceremonies at Westminster, with the monarch-to-be sitting in the Coronation Chair, including Queen Elizabeth in the 1950s.

The Stone was stolen from under the chair in 1950 by Scottish nationalists, though it was recovered in 1951. In 1996, the British government decided to officially return it to Scotland, and when it's not being used in coronation ceremonies, it's now held at Edinburgh castle.

Advertisement

5. One of its Greatest Treasures Is Hiding in Plain Sight

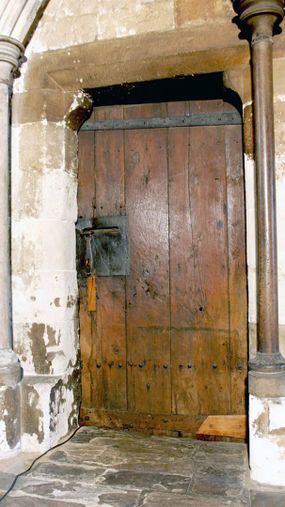

On the way into the Chapter House, visitors pass through a seemingly unremarkable, short wooden door. It's actually one of the last vestiges of the original abbey, and perhaps, says Cooper, Britain's oldest door.

"The oak door in the Chapter House vestibule has been dated by modern dendrochronology to the time of Edward the Confessor's reign, just before the Norman Conquest," he says. "The ring pattern reveals that the timber came from eastern England."

The door would originally have been about 9 feet (2.7 meters) tall, likely with an arched top. But, explains Cooper, it "was cut down to be recycled in Henry III's Abbey, built from 1245."

According to the official Westminster Abbey website, "After the planks were fitted together probably both faces were covered with cow hide, added to provide a smooth surface for decoration (no trace of painting remains). Then the ornamental iron hinges and decorative straps were fixed. Only one of the original straps survives today with hide trapped underneath it (on the inner face of the door) ... In the 19th century the fragments of cow hide were first noted and a legend grew up that this skin was human. It was supposed that someone had been caught committing sacrilege or robbery in the church and had been flayed and his skin nailed to this door as a deterrent to others."

In Westminster Abbey, even the simplest things are utterly remarkable.

Advertisement