The SCIF's first level of protection is limiting who has access to it. To enter the facility, you need a security clearance. (Some, though not all, top secret documents also require a person to be "read into" a particular code-word program to have access.)

"I'm not sure that it's ever been empirically proven, but the common wisdom is that the more people who know a secret, the more likely it is to leak out," Deitz says.

That puts officials who have the privilege of entering a SCIF under considerable pressure. "When you first get a security clearance and you're reading top secret documents, it's like, 'wow, this is really cool,'" Deitz recalls. But the novelty soon vanishes, when officials realize that they have to be tight-lipped around spouses and friends. "I teach now, and from time to time, I have to stop and think, can I say this?" Deitz says. "I mean, you have to be very, very careful about what you say and to whom you say it." Such caution "becomes part of your DNA," he says.

According to the U.S. government's exacting standards, SCIFs are required to have special walls, floors and ceilings that contain a minimum of 8 inches (20 centimeters) of concrete, doors equipped with special combination locks and deadbolts, and non-opening windows equipped with alarms if they're lower than 18 feet (5 meters) from the ground. SCIFs are designed to block both sound and electronic signals from being able to leave the room. Even the heating and ventilation ducts contain security devices.

That doesn't come cheap. The Pentagon requested nearly $34 million to build a SCIF at a U.S. Air Force Base back in 2011, according to correspondence with Congress.

There are similarly stringent rules about working with secrets inside a SCIF. Sensitive material is stored in safes, and it has to be put back and locked up when an official leaves. "That's one of the great things about working in the government, particularly on the defense side," Deitz says. "At the end of the day, you have a clean desk."

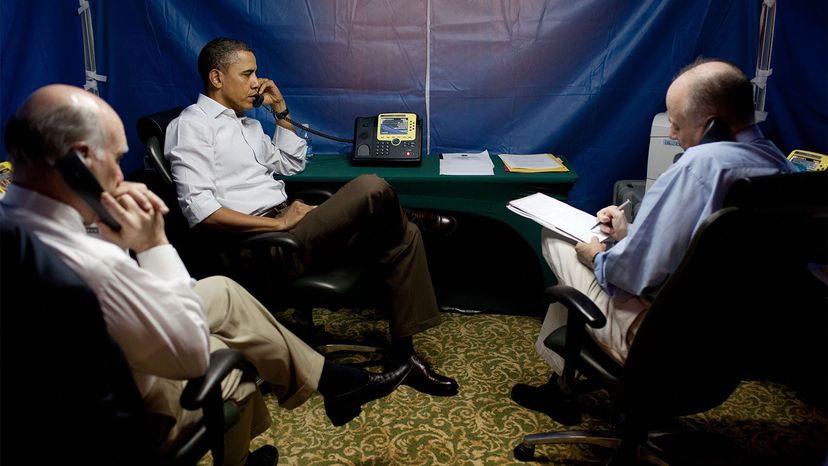

Cell phones aren't allowed inside a SCIF, though officials are allowed to make calls on a special secure phone. They are allowed to take notes — which themselves become classified material. Any paperwork that's discarded must go into special "burn bags," which are carefully handled until they're placed in an incinerator and destroyed.