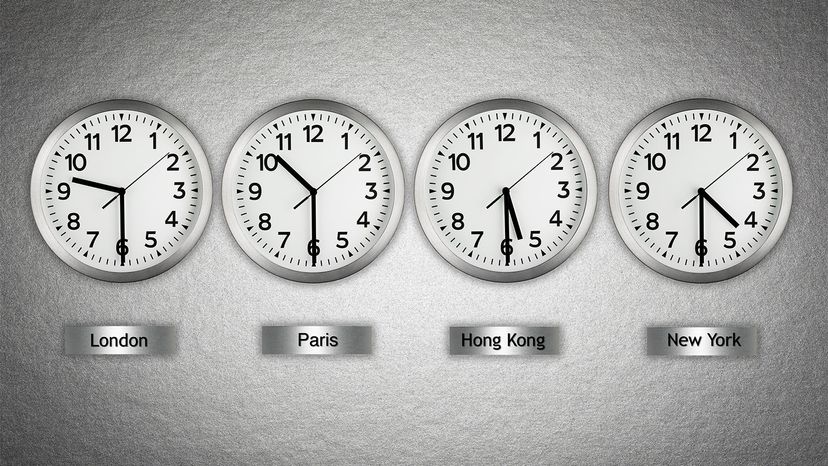

Travelers often grapple with the pesky task of adjusting their watches or laptop clocks to match local time. Ever missed a conference call because you forgot the time difference between Chicago, Los Angeles and New York City? Time zones aim to sync our clocks with the sun's position, but they can be quite the headache when criss-crossing regions or coordinating with far-off contacts.

It's strange to think that time zones were invented as a way of reducing confusion rather than causing it. Since solar time varies as you move even a short distance from one spot to another across the planet, for most of human history, the time of day varied everywhere.

Advertisement

"Time was only measured by placement of the sun, so the sundial dictated what time it was," explains Steve Hanke, a professor of applied economics at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Noon in London, for example, came 10 minutes earlier than noon in Bristol, 120 miles (193 kilometers) to the west. Even after people started using mechanical clocks in Europe in the 1300s, the inconsistencies persisted.