Plastics will outpace coal plants in the U.S. by 2030 in terms of their contributions to climate change, according to a report released Oct. 21 by Beyond Plastics, a project at Bennington College in Vermont. Yet policymakers and businesses are not currently accounting for the plastics industry’s full impact on climate change, allowing the industry to essentially fly "under the radar, with little public scrutiny and even less government accountability," the report says.

Judith Enck, president of Beyond Plastics and a former regional administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), says the report was intentionally released in the lead-up to the COP26 summit in Glasgow, Scotland, when world leaders will gather to discuss strategies for tackling climate change. "There's a little discussion on waste, but not much," Enck said in a video interview. "But plastics' contribution to climate change is not on the agenda."

Advertisement

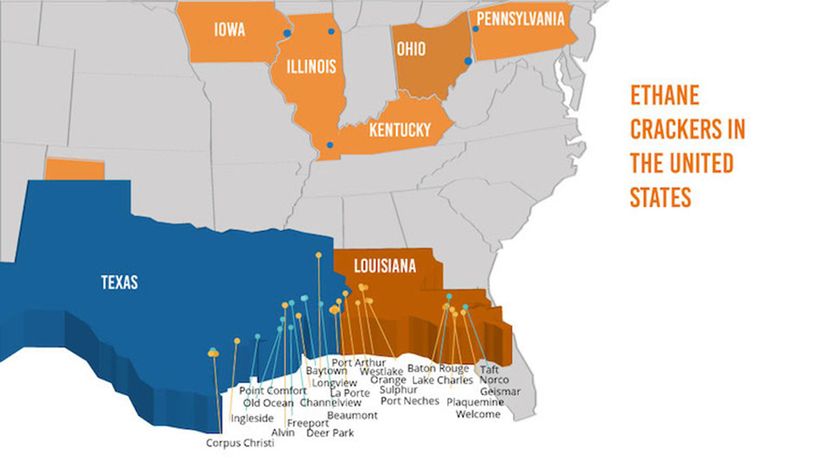

The report, "New Coal: Plastics and Climate Change," draws on public and private data sources to analyze 10 stages of plastic production in the U.S., including gas acquisition, transportation, manufacturing and disposal. It found that the U.S. plastics industry alone is presently responsible for at least 255 million tons (232 million metric tons) of greenhouse gases every year, the equivalent of about 116.5 gigawatts in coal plants. But this number is expected to rise as dozens of plastics facilities are currently under construction across the country, mainly in Texas and Louisiana, according to the report.

"What's quietly been happening under the radar is the petrochemical industry — the fossil fuel industry — has been ramping up investment in the production of plastics," Enck said. "Unless you live in the communities where this is taking place, people just don't know this."

Advertisement