"Any girl can be glamorous. All you have to do is stand still and look stupid."

In two short sentences, famed actress Hedy Lamarr managed to call gender stereotypes, beauty ideals and Hollywood artifice into question, using a hint of humor to make meaningful social commentary. In a sense, this succinct soundbite offers more insight into Lamarr's life and legacy than any headshot or publicity photo ever could, but understanding the context of the film star's words provides even more meaning to the boundary-breaking successes and unexpected influence she continues to have, two decades after her death.

Advertisement

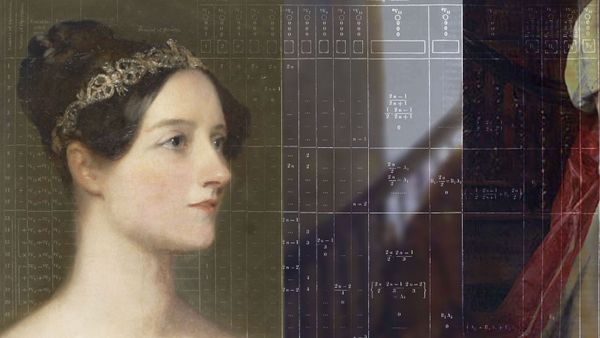

Born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler Nov. 9, 1914, the Austria native took an early interest in the performing arts, but seemed equally enchanted with science and engineering. "Hedy Lamarr grew up in a wealthy middle-class family in Vienna where she learned classical piano and enjoyed ballet, opera and chemistry," says Alexandra Dean, director of the documentary, "Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story," via email. "She loved tinkering with her gadgets and took apart her music box and smashed a light bulb to see how it worked."

By the time she was a teenager, Lamarr was turning heads for her stunning physical beauty — something that would both serve her and arguably hinder her success. "She became an actress because she thought it would be more fun than school, so she forged a note from her mother allowing her 10 hours away from classes and she went to her first audition," Dean says. At 17 years old, Lamarr scored her first film role in a German project called "Geld auf der Strase." She continued acting in European productions and in 1932, landed a controversial role in the scandalous-for-the-era film, "Exstase."

"She was too beautiful for her own good," Vincent Brook, author and UCLA media studies lecturer, says via email. "Her glamour queen, sex goddess persona kept her from being seen for the brilliant, complex person that she was."

Lamarr wed Austrian munitions dealer, Fritz Mandl, in 1933, but the marriage didn't last long. She later said of the union, "I knew very soon that I could never be an actress while I was his wife...He was the absolute monarch in his marriage...I was like a doll. I was like a thing, some object of art which had to be guarded — and imprisoned — having no mind, no life of its own." During their marriage, Lamarr was often spotted on Mandl's arm as he kept company with friends and business partners, many of whom had alleged ties to the Nazi party.

By 1937, Lamarr had had enough and fled her marriage, her former life and all ties to Austria. She headed to London, and soon signed a contract with Hollywood's Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio under the name Hedy Lamarr. Her first American film, "Algiers," kicked her career into high gear, and soon Lamarr was a household name.

"The sexist double-standard was reversed for Lamarr in other ways," Brook says. "Compared to German-accented male actors in Hollywood, who were relegated in the 1940s to supporting roles, mostly as Nazis, she and Marlene Dietrich, given their exotic/erotic allure, retained their marquee value."

Advertisement