For years, plenty of wild rumors and conspiracy theories have swirled around an 840-acre (340-hectare) speck of land a mile-and-a-half off New York's Long Island, home to a high-security federal research facility that Internet-fueled urban legends have made into the East Coast's equivalent of Area 51. Some have speculated that animal-human hybrids and biological warfare weapons are being developed inside the Plum Island Animal Disease Center, opened by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) in the 1950s and under the control of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security since 2003.

"I've had questions about Nazi scientists, alien technology and genetically-modified monsters," says John Verrico, a spokesman for Homeland Security's Science and Technology Directorate.

Advertisement

But inside the security fences and biocontainment area checkpoints (described in the unredacted parts of this 2007 government report), government researchers work to stave more tangible threats — foreign animal diseases such as foot-and-mouth disease and African swine fever, which have the potential to wreak havoc with the U.S. food supply if they ever spread across the nation's farms.

In the U.S., which hasn't had an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease since 1929, an outbreak of the highly contagious affliction could cause "billions and billions of dollars" in economic losses, Verrico says, because infected farm animals would have to be culled from herds and destroyed. Meat exports would come to a halt until the disease was eradicated, and consumers might face shortages of meat and dairy products. Farmers who produce animal feed would be harmed as well. A 2001 outbreak in the U.K. cost that nation the equivalent of more than $10 billion, according to the BBC.

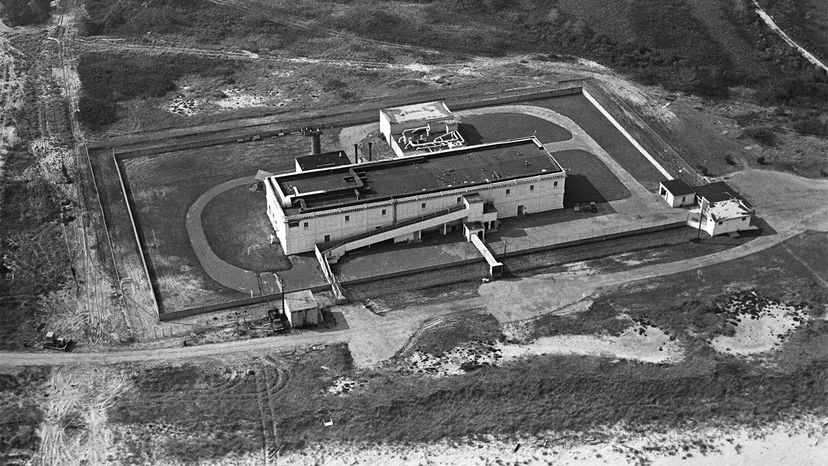

That longstanding danger led Congress to authorize the Department of Agriculture to create a laboratory to fight animal diseases back in the 1950s, with one major condition — the facility had to be located on an island, to reduce the danger of pathogens or infected animals escaping and spreading to farms, according to this September 1956 booklet. Plum Island, the site of the U.S. Army's Fort Terry from 1879 to 1948, fit that criteria.

Advertisement