Key Takeaways

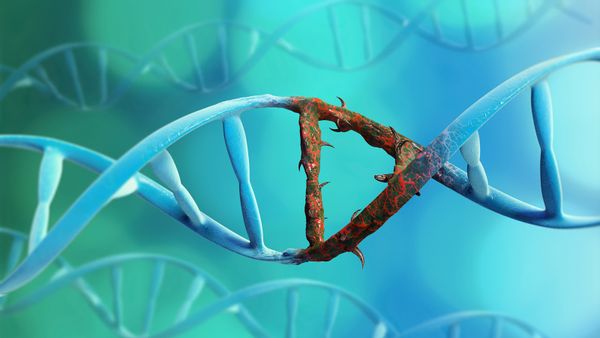

- Conditions where an organism has two genetically distinct types of DNA, including genetic chimerism and microchimerism, are more frequent than once believed.

- Beyond genetic origins, chimerism can occur through organ or tissue transplants and blood transfusions, and it is commonly observed as microchimerism during and after pregnancy.

- The existence of chimerism challenges conventional understanding in medicine, forensics and legal systems regarding individual identity and DNA analysis.

When Taylor Muhl, a California-based singer, asked a doctor to investigate the birthmark that demarcated the left side of her torso, she wondered what role the ruddy patch might play — if any — in a series of seemingly disparate health conditions she had experienced most of her life.

“Everything on the left side of my body is slightly larger than the right side,” Muhl says. “I have a double tooth in the left side of my mouth and many sensitivities and allergies to foods, medications, supplements, jewelry and insect bites.”

Advertisement

While Muhl says she hoped for answers, what she discovered was shocking. Her "birthmark" wasn't a birthmark at all. She actually carried the genetic code of her twin, a sister Muhl had absorbed while still in the womb.

Advertisement