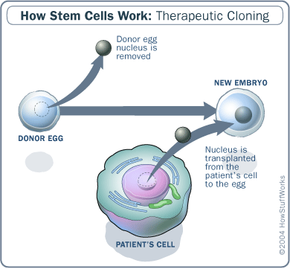

In order to understand how organ cloning might work, let's first talk about cloning itself. The most common method of therapeutic and reproductive cloning is somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT). SCNT involves removing the nucleus from a donor egg, and replacing it with the DNA from the organism meant to be cloned.

Scientists could potentially clone organs with somatic cell nuclear transfer by cloning human embryos, extracting the stem cells from the blastocyst, and stimulating the stem cells to differentiate into the desired organ. Coaxing a human stem cell to become a liver, for instance, will require further research. Scientists can reverse engineer cell differentiation processes to understand what chemical or physical signals stem cells receive to properly differentiate.

Research into human therapeutic cloning has largely come to a halt in the United States. Aside from bioethical issues, there's a lack of available human eggs for research. Laws and ethical regulations from the National Academy of Sciences and the International Society for Stem Cell Research prohibit monetary compensation for females who donate their eggs for embryonic stem cell research. [source: NCBI]

Coupled with the newness of the science and the potential risks involved with egg donation, stem cell researchers have been hard pressed to find donors. And given the low rate of success with embryonic cloning in general, researchers need an abundance of eggs if they hope to achieve progress. To compensate for the human egg scarcity, Ian Wilmut, who cloned Dolly the sheep, has suggested injecting human DNA into animal eggs instead [source: Britannica].

Nevertheless, advancements in therapeutic cloning have been made in animal studies. In March 2008, researchers removed skin cells from mice with Parkinson's disease to test a way to use stem cells as an effective treatment. They inserted the DNA from those skin cells into enucleated eggs (eggs with the nuclei removed) and created cloned mice embryos, via SCNT [source: ScienceDaily].

After extracting stem cells from the cloned embryos, the researchers developed autologous dopamine neurons from them, which are the nerve cells affected by Parkinson's. After implanting the new neurons into the mice, the test animals exhibited signs of recovery [source: ScienceDaily].

Xenotransplantation, or transplanting animal organs into humans, has also been examined as a potential source for organ transplants. But if our bodies sometimes reject transplanted organs from other humans, how would they react to animal organs?

In 2002, University of Missouri scientists cloned pigs that lack one of two genes called GATA1, which are primarily responsible for inducing that rejection response in humans [source: CNN]. Though primates would make more genetically suitable candidates for xenotransplantation, pigs are the best alternative until monkey cloning is a more viable option [source: Human Genome Project].

Future stem cell development for growing replacement organs may not even require cloning. In February 2008, a group of scientists at the University of California, Los Angeles derived stem cells from adult human skin cells. They were able to do so by controlling four regulator genes that influence cell differentiation [source: ScienceDaily].

By reprogramming the cells to act as stem cells, the altered skin cells became pluripotent and were called induced pluripotent stem cells. A few months later, Dutch researchers extracted adult stem cells from cellular material left over from open heart surgeries [source: ScienceDaily]. They used those stem cells to grow heart muscle cells, without the use of embryonic stem cells or cloning [source: ScienceDaily].

Because of the ethical gray areas surrounding embryonic stem cell research, people have reacted more positively to alternative methods like the ones described above. In theory, we should be able to eventually grow new organs from stem cells. But the technological advances discussed above indicate that cloning might not be necessary to harness those valuable cells.