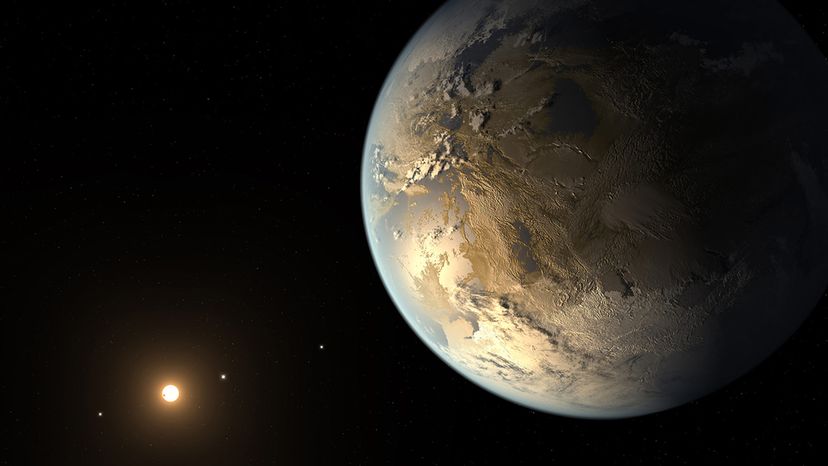

The discovery of Kepler-186f in April 2014 was significant because scientists believe planets able to support life will likely be Earth-sized, have a rocky or solid surface, contain liquid water and have a habitable atmosphere — essentially, they'll be planets very much like Earth.

They believe this because, to date, Earth is the only known example in the entire universe of a habitable planet, says Dr. Steve Howell, a senior NASA research scientist who worked on the Kepler mission.

Kepler-186f was the first Earth-size planet found orbiting within its star's habitable zone or Goldilocks zone, the area where liquid water (as opposed to water vapor) could exist on a planet's surface. An orbiting planet can't be too hot nor too cold in order for liquid water to be present.

Many planets had been identified orbiting within their star's habitable zone before Kepler-186f was discovered. But they were all at least 40 percent larger than Earth. In contrast, Kepler-186f had a radius just 1.11 times that of Earth. This small, Earth-like size is important, as it's the smaller planets that tend to be rocky, with terrain that could potentially support trees, plants and land for living. Earth-size planets also tend to have lighter, more breathable atmospheres. In contrast, large planets such as Jupiter and Saturn often have atmospheres filled with inhospitable gasses like hydrogen and helium.

Scientists have yet to determine Kepler-186f's mass and composition, so there's still a lot to learn. But they do know that it's part of a five-planet star system about 500 light-years from Earth in the constellation Cygnus. They also know the planet orbits an M dwarf star (aka a red dwarf) every 130 days. This dwarf star has about half of the mass of the sun.

More than 70 percent of the stars in the Milky Way galaxy are M dwarfs, a star classification indicating stars that are small, cool and dim. Any planet orbiting an M dwarf must be in a relatively tight orbit around the host star for it to receive enough warmth from the star to support life. That can be problematic, as M dwarfs are prone to large flares, or gas ejections, says Howell.

"Those flares, if they're strong enough, can go to a planet world that's very close to them and they could, for example, destroy that planet's atmosphere or life, if life existed on that planet," he says.