When George Washington was on his deathbed in 1799, he signaled for his secretary, Tobias Lear, and whispered hoarsely, "I am just going. Have me decently buried; and do not let my body be put into the Vault in less than three days after I am dead."

Those were Washington's final words, careful instructions from a man who wasn't afraid of death itself, but, like many people of his era, was deathly afraid of being buried alive.

Advertisement

In Washington's day and throughout the 19th century, the specter of "premature burial" felt very real. Medical science was in its infancy and death could strike from anywhere: common illnesses, infected wounds or fast-spreading outbreaks of smallpox. With so much death and so few scientific tools (even primitive stethoscopes weren't around until the 1820s), it went unquestioned that plenty of people were being buried while "not quite dead."

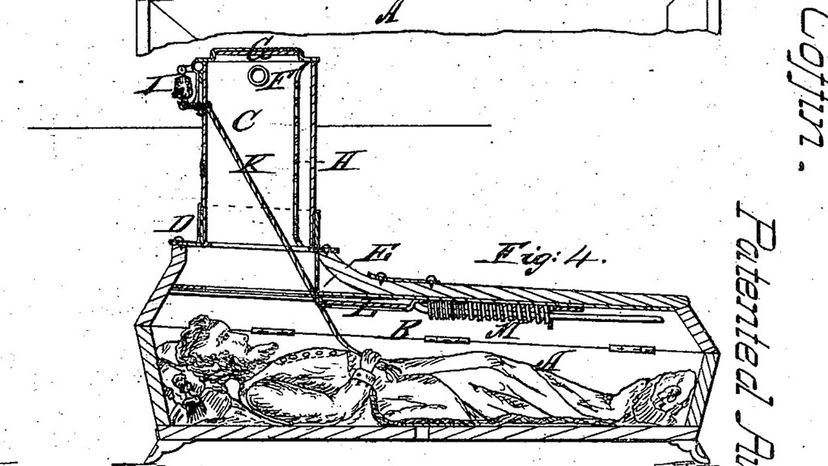

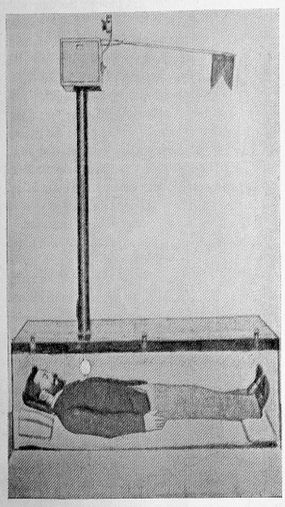

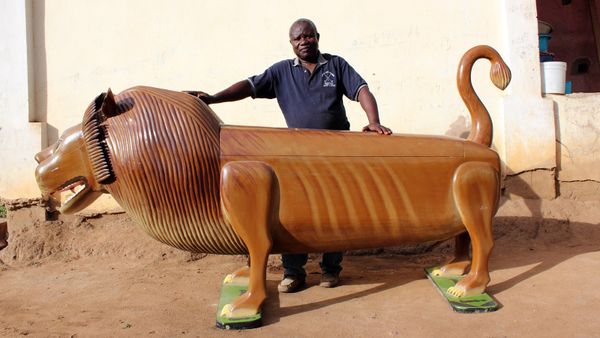

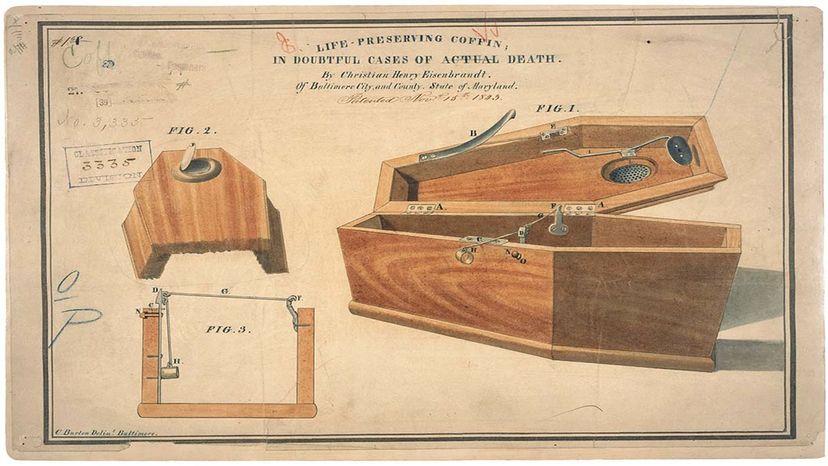

The acute fear of being buried alive — dubbed taphephobia (taphe is Greek for burial) — was part of a larger obsession with death that gripped the western world in the 19th century. One of the wildest ways that taphephobia manifested was through the invention of "safety coffins" (aka "security coffins"), tricked-out caskets that provided a way for prematurely buried people to escape from 6 feet under.

Advertisement