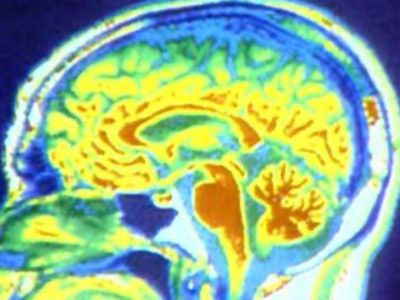

Every animal you can think of -- mammals, birds, reptiles, fish, amphibians -- has a brain. But the human brain is unique. Although it's not the largest, it gives us the power to speak, imagine and problem solve. It is truly an amazing organ.

The brain performs an incredible number of tasks including the following:

Advertisement

- It controls body temperature, blood pressure, heart rate and breathing.

- It accepts a flood of information about the world around you from your various senses (seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting and touching).

- It handles your physical movement when walking, talking, standing or sitting.

- It lets you think, dream, reason and experience emotions.

All of these tasks are coordinated, controlled and regulated by an organ that is about the size of a small head of cauliflower.

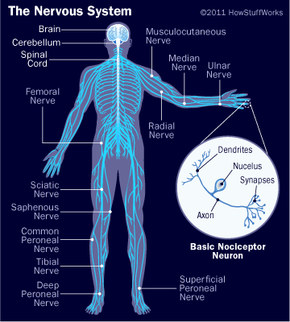

Your brain, spinal cord and peripheral nerves make up a complex, integrated information-processing and control system known as your central nervous system. In tandem, they regulate all the conscious and unconscious facets of your life. The scientific study of the brain and nervous system is called neuroscience or neurobiology. Because the field of neuroscience is so vast -- and the brain and nervous system are so complex -- this article will start with the basics and give you an overview of this complicated organ.

We'll examine the structures of the brain and how each section controls our daily functions, including motor control, visual processing, auditory processing, sensation, learning, memory and emotions.