In detective movies or TV shows like "CSI," photographers swarm in and take countless pictures of a crime scene. They twist and turn their cameras haphazardly as agents discuss leads over the background hum of the photographs' flash explosions. But how does crime scene photography really go down? Since its purpose is to record evidence that will be admissible in court, it's hardly a haphazard operation.

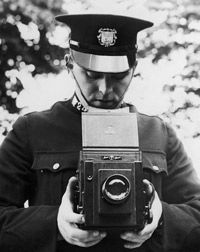

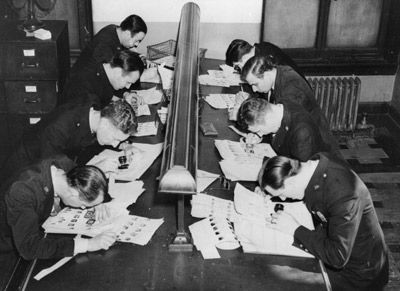

Crime scene photography, also called forensic photography, has been around almost as long as the camera itself. Criminologists quickly realized that such technology could freeze time -- creating a supposedly incontestable record of a crime scene, a piece of evidence or even a body. The 19th century French photographer Alphonse Bertillon was the first to approach a crime scene with the systematic methods of an investigator. He'd capture images at various distances and take both ground level and overhead shots.

Advertisement

Today, forensic photographs are essential for investigating and prosecuting a crime. This is because most evidence is transitory: Fingerprints must be lifted; bodies must be taken away and examined; and homes or businesses must be returned to their normal state. Photographs help preserve not only the most fleeting evidence -- like the shape of a blood stain that will soon be mopped up -- but also the placement of items in a room and the relation of evidence to other objects. Such images can prove vital to investigators long after the crime scene is gone.

So how do crime scene photographers go about their business? Find out in the next section.

Advertisement