There are records of fingerprints being taken many centuries ago, although they weren't nearly as sophisticated as they are today. The ancient Babylonians pressed the tips of their fingertips into clay to record business transactions. The Chinese used ink-on-paper finger impressions for business and to help identify their children.

However, fingerprints weren't used as a method for identifying criminals until the 19th century. In 1858, an Englishman named Sir William Herschel was working as the Chief Magistrate of the Hooghly district in Jungipoor, India. In order to reduce fraud, he had the residents record their fingerprints when signing business documents.

A few years later, Scottish doctor Henry Faulds was working in Japan when he discovered fingerprints left by artists on ancient pieces of clay. This finding inspired him to begin investigating fingerprints. In 1880, Faulds wrote to his cousin, the famed naturalist Charles Darwin, and asked for help with developing a fingerprint classification system. Darwin declined, but forwarded the letter to his cousin, Sir Francis Galton.

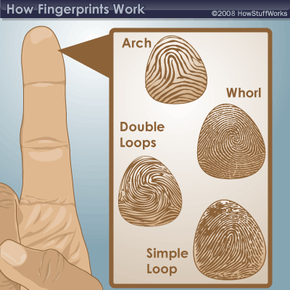

Galton was a eugenicist who collected measurements on people around the world to determine how traits were inherited from one generation to the next. He began collecting fingerprints and eventually gathered some 8,000 different samples to analyze. In 1892, he published a book called "Fingerprints," in which he outlined a fingerprint classification system -- the first in existence. The system was based on patterns of arches, loops and whorls.

Meanwhile, a French law enforcement official named Alphonse Bertillon was developing his own system for identifying criminals. Bertillonage (or anthropometry) was a method of measuring heads, feet and other distinguishing body parts. These "spoken portraits" enabled police in different locations to apprehend suspects based on specific physical characteristics. The British Indian police adopted this system in the 1890s.

Around the same time, Juan Vucetich, a police officer in Buenos Aires, Argentina, was developing his own variation of a fingerprinting system. In 1892, Vucetich was called in to assist with the investigation of two boys murdered in Necochea, a village near Buenos Aires. Suspicion had fallen initially on a man named Velasquez, a love interest of the boys' mother, Francisca Rojas. But when Vucetich compared fingerprints found at the murder scene to those of both Velasquez and Rojas, they matched Rojas' exactly. She confessed to the crime. This was the first time fingerprints had been used in a criminal investigation. Vucetich called his system comparative dactyloscopy. It's still used in many Spanish-speaking countries.

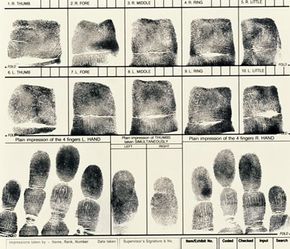

Sir Edward Henry, commissioner of the Metropolitan Police of London, soon became interested in using fingerprints to nab criminals. In 1896, he added to Galton's technique, creating his own classification system based on the direction, flow, pattern and other characteristics of the friction ridges in fingerprints. Examiners would turn these characteristics into equations and classifications that could distinguish one person's print from another's. The Henry Classification System replaced the Bertillonage system as the primary method of fingerprint classification throughout most of the world.

In 1901, Scotland Yard established its first Fingerprint Bureau. The following year, fingerprints were presented as evidence for the first time in English courts. In 1903, the New York state prisons adopted the use of fingerprints, followed later by the FBI.

But how has fingerprinting changed since the 19th century? In the next section, we'll find out about modern fingerprinting techniques.