George Washington Carver was born around 1864 near Diamond Grove, Missouri, under conditions of servitude. As a young boy, he had a deep fascination with plants and spent a lot of his time studying and experimenting with them. He developed a reputation in his local community for his ability to diagnose and treat plant diseases, which led to him being called "The Plant Doctor."

His educational journey began at Simpson College in Indianola, Iowa, where he attended for a short time before transferring to Iowa State Agricultural College (now known as Iowa State University) in Ames, Iowa, in 1891. In fact, he became the first Black American student to enroll at Iowa State.

After completing his undergraduate studies, Carver pursued a master's degree in agricultural science at the same institution. It was during this time that he conducted research and made significant contributions to the field of agriculture.

Despite the racial challenges he faced during his time, Carver went on to establish himself as a pioneering Black American scientist at the school. While he is widely celebrated for his groundbreaking work with peanuts, Carver's research extended to other crops like soybeans and sweet potatoes.

The Tuskegee Institute

In 1896, Carver accepted an invitation from Booker T. Washington to lead the Agriculture Department at the recently formed Tuskegee Institute, where he would remain — teaching and conducting laboratory work — for most of his life.

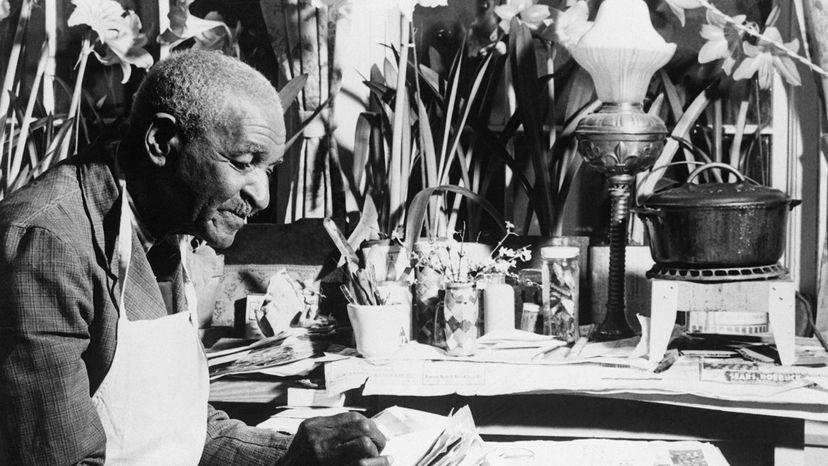

At Tuskegee, George Washington Carver's work included serving as a teacher, testing crop varieties and fertilizers, writing bulletins for farmers and managing research at his experiment station.

Within the esteemed walls of Tuskegee, Carver's multifaceted talents shone brightly. He wasn't just an educator imparting knowledge; he was an experimenter, rigorously testing various crop varieties and exploring the efficacy of different fertilizers. With a keen understanding of the challenges local farmers faced, Carver penned informative bulletins, offering them insights and advice.

His commitment extended to hands-on research at his experiment station, where he sought to discover and propagate sustainable agricultural practices. Under his stewardship, the Tuskegee Institute's agricultural initiatives flourished, becoming a beacon of innovation and knowledge for the broader farming community.

Working With Cotton

While much of Carver's work was devoted to promoting alternatives to cotton for Southern farmers, he didn't completely dismiss the plant. At Tuskegee, he experimented with different varieties of cotton and issued bulletins instructing farmers on crop rotation to rejuvenate cotton fields. He also developed cotton fiber for rope, twine and paper and made a road-paving surface from cotton stalks.

Indeed, few things missed Carver's gaze, as he is credited with making a range of products as varied as concrete reinforcing built from sawdust, wood shavings, synthetic marble and vegetable dyes.