Key Takeaways

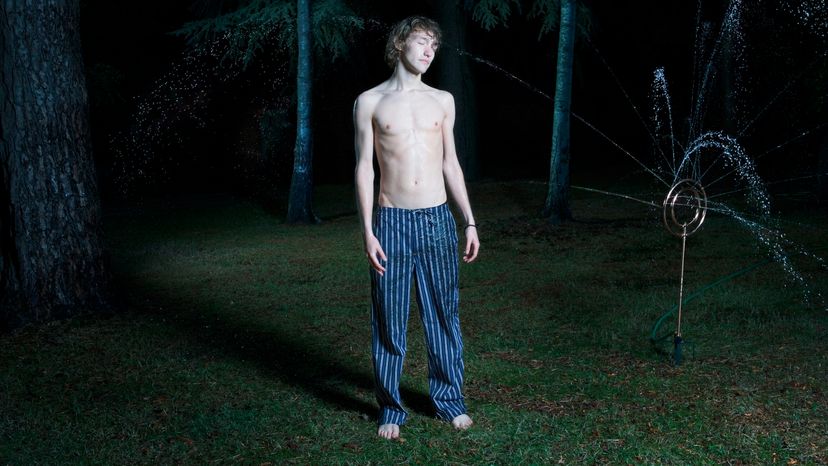

- Sleepwalking, or somnambulism, is characterized by walking or performing other complex behaviors while in a state of partial arousal from deep, non-REM sleep.

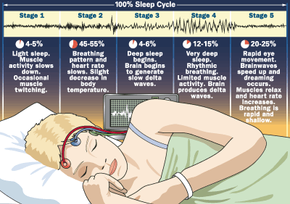

- Sleepwalking occurs during deep sleep stages. It involves a disconnect between brain functions, where the brain is less active but the body can still move.

- Factors contributing to sleepwalking include genetics, sleep deprivation, stress and some medications.

Sleepwalking is an intriguing phenomenon. The fact that you're sleeping while performing physical feats is pretty amazing. How can a person be unconscious but still coordinate his or her limbs in order to walk, talk and, sometimes, even drive? How do we know when we're really awake?

Sleepwalking is also known as somnambulism, so add that to your SAT vocab. It's classified as a parasomnia, an abnormal behavior during sleep that's disruptive. Common parasomnias include bed-wetting and teeth grinding. Drs. Hobson and Silvestri describe parasomnias as "errors in timing and balance" in the brain as it transitions between waking and sleeping [source: sleepwalking5.htm">Hobson].

Advertisement

Think of how complex the brain is and how many tasks it performs: It keeps you breathing, it reminds your heart to beat, it records all the memories of your life, and it enables you to laugh, cry, love and converse. Now think of how you sleep, how your body moves from dreams to no dreams and back again, how you might steal covers from your partner or snore or move around, how sometimes you wake up rested and other days you wake up anxious. It's a complex process controlled by a complex organ: There's plenty of room for glitches.

What makes a sleeping body rise? People used to think that sleepwalkers were acting out their dreams and subconscious desires and fears. Take Shakespeare's Lady Macbeth, who during the day conceals the depth of her treachery, but at night in her sleep confesses her guilt. Others associate it with the occult, as in "Dracula" when the vampire is finally able to sink his teeth into Lucy while she sleeps. Others insist that it's purely a physical response, illustrated by the case of the title character in Bellini's opera "La Sonnambula," who incurs all sorts of trouble by the innocent actions she performs while she sleeps (more on this later).

In this article, we'll explore the whys of sleepwalking: why it happens the way it does, why it happens at all and why it's so fascinating.

Advertisement