While the majority of vampire scholars focus on the cultural roots of vampire lore, some historians have looked to physical origins. There is no scientific evidence of actual vampires, but there are a number of real medical conditions that might result in vampiric behavior or appearance.

Medical Conditions Mimicking Vampirism

One of the most interesting "vampire diseases" is porphyria. Porphyria is a rare disease characterized by irregularities in production of heme, an iron-rich pigment in blood. People with the more severe forms of porphyria are highly sensitive to sunlight, experience severe abdominal pain and may suffer from acute delirium.

One possible treatment for porphyria in the past might have been to drink blood, to correct the imbalance in the body (though there's no clear evidence of this). Some porphyria sufferers do have reddish mouths and teeth, due to irregular production of the heme pigment. Porphyria is hereditary, so there may have been concentrations of sufferers in certain areas throughout history.

A more likely physical root of vampirism is catalepsy, a peculiar physical condition associated with epilepsy, schizophrenia and other disorders that affect the central nervous system.

During a cataleptic episode, a person essentially freezes up: The muscles become rigid, so that the body is very stiff, and the heart rate and respiration slow down. Someone suffering from acute catalepsy could very well be mistaken for a corpse.

Today, doctors have the knowledge and tools to accurately determine whether or not someone is alive, but in the past, people would decide based only on appearance. Embalming was unknown in most of the world until relatively recently, so a body would have been put right in the ground as is.

A cataleptic episode can last many hours, even days, which would allow enough time for a burial. When the person came to, he or she might have been able to dig themselves out and return home. If the person did suffer from a psychological disorder, such as schizophrenia, he or she might have exhibited the strange and disturbing behavior associated with vampires.

Decomposition and Misunderstandings of Death

The behavior of actual corpses might have suggested vampirism as well. After death, fingernails and hair often appear to continue growing because the surrounding skin recedes, which may give the impression of life. Gases in the body expand, extending the abdomen, as if the body had gorged itself.

If you were to stake a decomposing corpse, it could very well rupture, draining all sorts of fluids. This might be taken as evidence that the corpse had been feeding on the living.

Psychological Roots of Vampire Lore

While these conditions might have fueled a fear of the undead, the origins of vampire mythology are most likely psychological rather than physical. Death is one of the most mysterious aspects of life, and all cultures are preoccupied with it to some degree.

One way to get a handle on death is to personify it — to give it some tangible form. At their root, Lamastu, Lilith and similar early vampires are explanations for a terrifying mystery, the sudden death of young children and fetuses in the womb. The strigoi and other animated corpses are the ultimate symbols of death; they are the actual remains of the deceased.

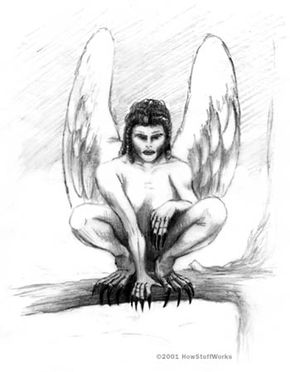

Vampires also personify the dark side of humanity. Lilith, Lamastu and the other early vampire demonesses are the opposite of the "good wife and mother." Instead of caring for children and honoring a husband, they destroy babies and seduce men.

Similarly, undead vampires feed on their family, rather than supporting it. By defining evil through supernatural figures, people can get a better handle on their own evil tendencies and externalize them.

The appearance of so many vampire-like monsters throughout history, as well as our continued fascination with vampires, demonstrates that this is a universal response to the human condition. It's simply human nature to cast our fears as monsters.

A Psychic Twist

One modern variation on the vampire legend is the "psychic vampire." These self-identified vampires claim that they crave psychic energy from others and have the power to drain it without the person's knowledge.

Psychic vampires typically attempt to drain life-force energy through meditation and concentration. If they do not feed, they say, they will become weak as if they had not eaten.

According to some believers, this sort of vampire has been around for thousands of years. Some claim this phenomenon inspired the undead vampires of folklore.

Real Bloodsuckers

In many modern movies and books, vampires can take the form of a vampire bat, a real animal that feeds on blood. In actuality, vampire bats don't usually kill their prey, and they pose little threat to humans. In fact, they are small, reclusive, docile animals.

Vampiric shape-shifters go back thousands of years, but the particular connection to vampire bats is fairly recent. Vampire bats are only found in Central America and South America, so the Europeans and Asians who originally conceived of these monsters didn't know about them. When European explorers discovered the strange animals, they were soon incorporated into the vampire myth.