In the last section, we saw that a piece of soft bulletproof material works in the same basic way as the net in a soccer goal. Like a soccer goal, it has to "give" a certain amount to absorb the energy of a projectile.

When you kick a ball into a soccer goal, the net is pushed back pretty far, slowing the ball down gradually. This is a very efficient design for a goal because it keeps the ball from bouncing out into the field. But bulletproof material can't give this much because the vest would push too far into the wearer's body at the point of impact. Focusing the blunt trauma of the impact in a small area can cause severe internal injuries.

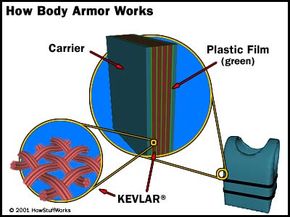

Bulletproof vests have to spread the blunt trauma out over the whole vest so that the force isn't felt too intensely in any one spot. To do this, the bulletproof material must have a very tight weave. Typically, the individual fibers are twisted, increasing their density and their thickness at each point. To make it even more rigid, the material is coated with a resin substance and sandwiched between two layers of plastic film.

A person wearing body armor will still feel the energy of a bullet's impact, of course, but over the whole torso rather than in a specific area. If everything works correctly, the victim won't be seriously hurt.

Since no one layer can move a good distance, the vest has to slow the bullet down using many different layers. Each "net" slows the bullet a little bit more, until the bullet finally stops. The material also causes the bullet to deform at the point of the impact. Essentially, the bullet spreads out at the tip, in the same way a piece of clay spreads out if you throw it against a wall. This process, which further reduces the energy of the bullet, is called "mushrooming."

No bulletproof vest is completely impenetrable, and there is no piece of body armor that will make you invulnerable to attack. There's actually a wide range of body armor available today, and the types vary considerably in effectiveness. I

We just saw that modern soft body armor consists of several layers of super-strong webbing. This material disperses the energy of a bullet over a wide area, preventing penetration and dissipating blunt trauma. This sort of armor, as well as hard armor, ranges considerably in effectiveness, depending on the materials used as well as the armor design.

In the United States, body armor levels are certified by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), which is an agency of the U.S. Department of Justice. The levels are I, II-A, II, III-A, III, and IV. Based on extensive laboratory tests, researchers classify any new body-armor design into one of seven categories: Category I body armor offers the lowest level of protection, and category IV offers the highest. The body-armor classes are often described by what sort of weaponry they guard against. The lowest-level body armor can only be relied on to protect against bullets with a relatively small caliber (diameter), which tend to have less force on impact. Some higher-grade body armor can protect against powerful shotgun fire. Categories I through III-A are soft and concealable. Type III is the first one to utilize hard or semi-rigid plates.

Generally speaking, armor with more layers of bulletproof material offers greater protection. With some bulletproof vests, you can add layers. One common design is to fashion pockets on the inside or outside of the vest. When you need extra protection, you insert metal or ceramic plates into the pockets. When you don't need as much protection, you can wear the vest as ordinary soft armor.

To determine how effective a particular armor design is, researchers shoot it with all sorts of bullets, at all sorts of angles and distances. For a piece of armor to be considered effective against a particular weapon at a particular range, it has to stop the bullet without causing dangerous blunt trauma. The researchers determine blunt trauma by molding a layer of clay onto the inside of the armor. If the clay is deformed more than a certain amount at the point of impact, the armor is considered ineffective against that weaponry.