Some of history's most persistent structures are the aqueducts built by ancient Romans to carry water from mountains to heavily populated areas. Many still operate today, more than 2,000 years after they began their service. What makes aqueducts so strong is the cascade of arches holding up the structure.

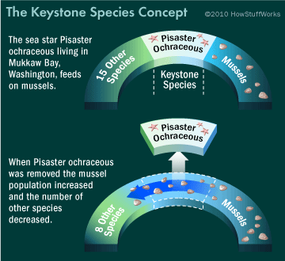

If you examine one of these arches, you'll see it consists of a series of bricks — what engineers call voussoirs — supported at the center by a keystone. The keystone gives the arch its strength and stability. When it's in position, the arch can stand indefinitely. Remove it, and the whole structure collapses. Now, what does this have to do with the entire ecosystem?

Advertisement

In 1969, a zoologist named Robert T. Paine realized that certain species in an ecosystems function just like the keystone in a Roman arch, and he coined the term keystone species to describe them. Such a species plays an essential role in the structure, functioning or productivity of an ecosystem and, like its bridge counterpart, keeps that particular ecosystem from falling apart. So, what are considered keystone species?