Around 66 million years ago, the last of the dinosaurs (other than birds) died out.

So did the pterosaurs, the dinosaurs' reptilian cousins that flew around on membranous wings. Joining them in death were the era's giant marine reptiles, like the four-flippered plesiosaurs and the mosasaurs of "Jurassic World" fame.

Advertisement

It was all part of a global mass extinction event. During that bleak chapter in our planet's history, approximately 75 percent of all the species alive at the time were killed off.

So, what happened? That question has inspired controversy for decades. But in 1978, a hidden piece of the puzzle was discovered along the Mexican Gulf Coast.

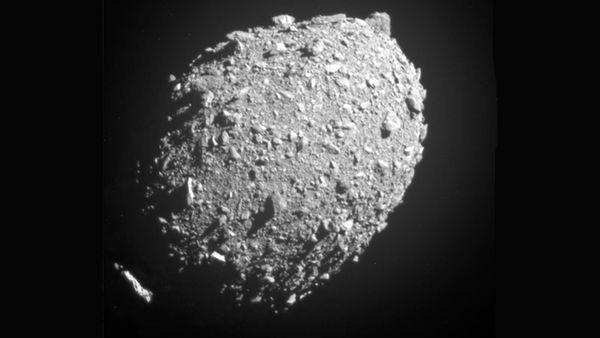

Geologists working for the Pemex petroleum company were conducting a magnetic survey in the Caribbean at the time. Guided by their instruments, they noticed something the naked eye couldn't detect: a strange arc buried under the seabed, just north of Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula.

Further research showed that the arc was part of a massive underground crater.

Straddling the peninsula's northern shoreline and some of the adjacent ocean floor, the crater is absolutely huge, with an estimated diameter of between 112 and 124 miles (180 and 200 kilometers).

All these years later, we're still grappling with the implications of that fateful discovery.

The '78 survey gave scientists their first look at the calling card of a giant extraterrestrial object. Perhaps it was created by an asteroid impact or even a comet. Whatever it was, we know the crater's maker smacked into Earth roughly 66 million years ago — coinciding with the disappearance of non-avian dinosaurs from the fossil record.

Advertisement