Key Takeaways

- Pinky toes are not essential for modern humans, offering minimal balance support.

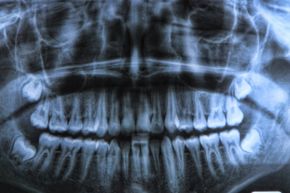

- Wisdom teeth are vestigial organs that often cause issues today, as human jaws have shrunk over evolutionary time.

Our bodies force us to a lot of dumb things. Consider that we have to breathe -- constantly -- to avoid death. You'd think that evolution would've provided a nice workaround so we could hold on to those calories, storing that energy for times when we need it, like those really long Monopoly games. Who doesn't get crabby and bored halfway through those?

But breathing has nothing on some of the straight-up needless or even harmful adaptations that are seen in not just humans, but animals in general. In the next few pages, we'll first explore the dumb adaptations (or lack thereof) that humans have suffered with. We'll then turn to some of the most bizarre, dangerous or simply unnecessary evolutionary quirks that have affected other members of the animal kingdom.

Advertisement

From the obnoxious wisdom teeth that crowd our mouth to the rather disturbing birth canal of the hyena, be prepared to find yourself a little resentful of all the ways evolution has done us wrong.