Parents who suspect that their child may have a genetic disorder have a new tool in their physician's diagnostic arsenal. One British physician has improved on an old practice of examining a person's face to look for traits that come from genetic disorders.

It's true. The shape of your face, along with certain facial characteristics, can be a sign that you suffer from a genetic disorder. As many as 17,000 genetic disorders have been diagnosed [source: Deccan Herald]. Around 700 of these diagnosed disorders display abnormal facial characteristics [source: Daily Mail]. A classic example is the genetic disorder Down syndrome. This condition occurs when children inherit an extra copy of chromosome 21, giving them 47 chromosomes, rather than the usual 46. Doctors can easily diagnose Down syndrome due to the unique facial and cranial characteristics associated with it. But what about rarer disorders?

Advertisement

Dr. Peter Hammond created a computer program to make diagnosing some of these rare disorders easier. The program provides an accurate diagnosis, which can help parents make better decisions about treatment and genetic counseling for their child.

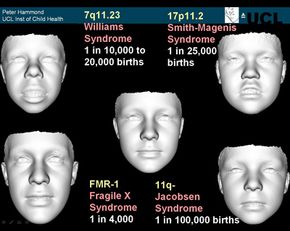

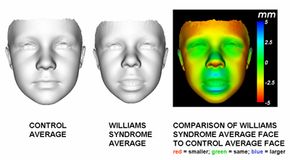

Dr. Hammond spent the last seven years traveling the globe collecting images of people with genetic disorders and entering them into a database he compiled. The program takes photos of children who share a genetic disorder, usually a series of 30 to 50, and creates a three-dimensional composite image for that disorder. When a physician encounters a suspected genetic disorder that has him stumped, he can introduce a photo of his patient into Hammond's database. The program examines facial traits, like the distance between eyes and the width of the nose, and compares traits found in the patient's image to those of the composites and comes up with possible diagnoses. As a control, Hammond also fed into his database images of children without a genetic disorder, creating a composite of a "normal" child.

For 30 of the 700 facially characteristic disorders, Hammond's program offers around 90 percent accuracy in diagnosis. These are generally the most easily recognizable conditions, such as Williams syndrome. People who suffer from this genetic disorder have short, upturned noses and mouths, along with a small jaw and a large forehead.

Williams syndrome is pretty rare -- some studies say it occurs in one out of every 7,500 births, while others say it's one in 10,000 births [source: OMIM]. But other genetic disorders are even rarer. For a doctor faced with a baffling condition that he has not encountered before, Hammond's program offers a chance to narrow the field. Determining which genes are associated with the possible diagnoses cuts down on the number of tests required to pinpoint the disorder. This can be important for worried parents who want to know what their child suffers from, as genetic tests can cost hundreds or thousands of dollars each [source: Science Direct].

Hammond's database has already discovered a new characteristic in autistics that can be used to diagnose autism spectrum disorder. The program found a "lopsided" effect in autistic people -- the result of one side of the brain being larger than the other side. The inventor-physician says he plans to further hone his database to be able to include factors like race and gender [source: BBC].

While his work is definitely furthering the field of medical diagnosis of genetic disorders, Hammond is actually building on an old foundation. Read on to find out about dysmorphology, the study of physical characteristics to diagnose disorders, as well as genetic counseling.

Advertisement