The field that may yield the most possibilities for treating PTSD in the future is neurology.

Studying the brain's functions has already turned up some interesting facts about how we process our fear response. One chemical that has been studied is called stathmin, and it allows us to form fear memories from our experience.

In a laboratory experiment, researchers treated mice to diminish their levels of stathmin. Those mice with lowered levels were less likely to be affected by panic (and less likely to "freeze") when confronted with traumatic experiences later [source: NIMH].

Another chemical, gastrin-releasing peptide, has been shown to signal a response in the brain. Research suggests that a lack of this chemical could lead to an increased chance that a person will form stronger fear memories [source: NIMH].

Brain Structures and Fear Memories

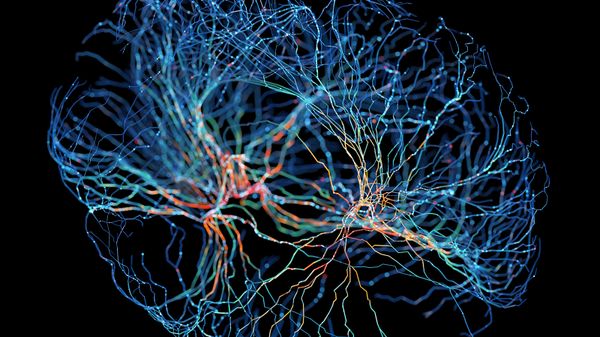

How we create and maintain our fearful memories of experiences is at the heart of physiological research on PTSD. Investigation into the amygdala has shown that this part of our brain helps us to learn how to not fear, as well as to fear. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex (PFC) appears to maintain our long-term fear memories.

Researchers have found that the size of this part of the brain may be related to the likelihood a person keeps fear memories after a traumatic event [source: NIMH]. Of course, environmental and social factors have their parts to play in whether people with genetic predispositions to PTSD actually get it.

Emerging Treatments and Techniques

Researchers at Fort Bragg, N.C., have studied soldiers who handle stressful situations better than others and believe they have found a chemical that's responsible for the difference. Neuropeptide Y is thought to be the brain's own anti-anxiety drug.

As we're exposed to a stressful or traumatic situation, our levels of this drug become depleted. The more depleted it becomes, the more fearful we become. Scientists are trying to synthesize neuropeptide Y to restore a person's depleted levels after a traumatic situation, and possibly guard against the development of PTSD.

Stellate ganglion blocks have also been tested. This procedure uses a local anesthetic injected above the clavicle to block the function of sympathetic nerves (the same ones responsible for the fight-or-flight response).

A 2008 study found that seven of nine patients given the block experienced relief of their PTSD symptoms, including one patient who had been suicidal for the previous two years. However, the benefits appeared to fade after two months [source: Hicky, et al].

MDMA (also known as ecstasy) has also been shown to lessen the effects of PTSD. The majority of patients in a 2012 study of the drug showed relief from their symptoms; some of these patients hadn't experienced any relief from other courses of treatments they'd taken [source: The Guardian]. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) has been shown to improve PTSD conditions as well.

The authors of a 2004 study of 20 male and female patients suffering from PTSD as a result of events like combat, assault and sexual abuse believe that the effects were the result of the magnetic coil stimulating neurons in the brain [source: VA Research Currents].

Virtual Reality and Remote Counseling

Also, remember that study of Detroit PTSD sufferers that found they had epigenetic changes to their immune system genes? There is growing evidence that injecting a person who has recently undergone a trauma (within the first few hours) with a low dose of regular hydrocortisone, a corticosteroid that suppresses the immune response, can prevent PTSD from taking hold later on. The studies are small, but the results are encouraging [source: Delahanty, et al].

Virtual reality is also being used to help treat people with PTSD. It has reduced chronic PTSD symptoms in Vietnam veterans and is particularly useful for people who can't or won't access their emotions in therapy.

A case study used virtual reality simulations of the Sept. 11 attacks on the World Trade Center as part of exposure therapy to help one woman recover from PTSD. She was exposed to her traumatic memory not by her own recollections, but as an active observer (for instance, virtual planes flew into virtual towers). The result was very positive. Her PTSD symptoms decreased by 90 percent [source: HITL].

Research into the viability and usefulness of delivering counseling via the internet or by phone is also being conducted. This kind of counseling could be helpful in cases of mass disasters that affect large numbers of people by delivering counseling to many people at the same time.

Operation Battlemind

The military is investigating techniques for "inoculating" soldiers from PTSD. The Walter Reed Institute of Research has developed a program of Resilience Training (formerly called "Battlemind") that helps soldiers strengthen themselves mentally in order to lessen susceptibility to PTSD.

This program stresses the development of traits like social interdependency and openness among soldiers and attempts to root out risk factors like avoidance. The program also aids in the transition from deployment status to civilian life.