Key Takeaways

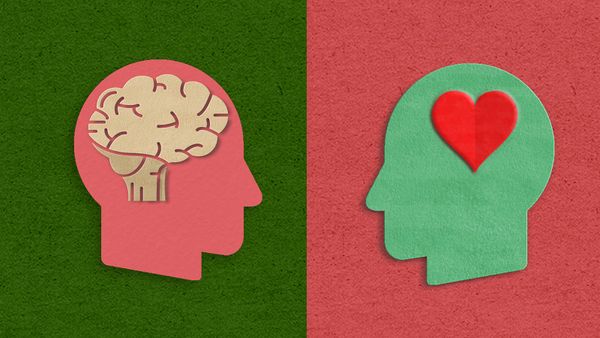

- Ordinary speech and prose affect the human brain but not in the same way as poetry, which activates specific areas of the brain that recognize its rhymes and rhythms and contemplate its imagery and layered meanings.

- The brain's reaction to poetry indicates a deep, intuitive connection to verse, suggesting that appreciation of poetry is within our neurological structure.

- Reading or listening to poetry not only stimulates emotional and aesthetic responses but also enhances cognitive functions like flexible thinking and the capacity to understand complex, multiple meanings, which can be beneficial in everyday decision-making.

Whether it's Alfred Lord Tennyson's "Ulysses" or Maya Angelou's "Caged Bird," there's something about reading or hearing a great poem that stimulates our minds, moving us to ponder the world from a new angle. And from a neuroscientific point of view, that's no accident.

In recent years, researchers have used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and other sophisticated tools to study how the human brain reacts to poetry. They've discovered, among other things, that the brain seems to be wired to recognize the rhymes and rhythms that poets use, and differentiate them from ordinary speech or prose. They've also found that contemplating poetic imagery and the multiple layers of meanings in poems activates specific areas of the brain — some of the same areas, in fact, that help us to interpret our everyday reality.

Advertisement

One reason poetry has such a potent effect upon us is that our brains seem to be wired to recognize it. In one newly published study in the journal Frontiers of Psychology, researchers at the UK's Bangor University read an assortment of sentences to a group of Welsh-speaking subjects. Some of the sentences conformed to the intricate poetic construction rules of Cynghanedd, a traditional form of Welsh poetry, while others didn't follow those rules. Though the subjects didn't know anything about Cynghanedd, they nevertheless categorized as "good" the sentences that followed the rules as compared to other sentences. The researchers also hooked up the subjects to EEG devices, and observed a distinctive burst of electrical activity in the subjects' brains that occurred in the fraction of a second after hearing the last word of a poetic line.

"I believe that our results argue for a profoundly intuitive origin of poetry," says Bangor psychology professor Guillaume Thierry, via email. "Poetry appears to be 'built in,' it is like a profound intuition, every human being is an unconscious poet."

Poetry also seems to affect specific areas of the brain, depending upon the degree of emotion and the complexity of the language and ideas. In a study published in 2013 in Journal of Consciousness Studies, researchers at the UK's University of Exeter had participants lay inside an fMRI scanner while they read various texts on a screen. The selections ranged from deliberately dull prose — such as a section from a heating equipment installation manual — and passages from novels to samples from various poems, a few of which the subjects had identified as their favorites. The subjects had to rate the texts on qualities such as how much emotion they aroused, and how "literary," or difficult to contemplate, they were.

The researchers found that the higher the degree of emotiveness that subjects assigned to a sample, the more activation that the scans showed in areas on the right side of the brain — many of the same ones identified in a 2001 study as being activated by music that moved listeners to feel chills or shivers down their spines. The examples rated as more "literary," in contrast, lit up areas mostly on the left side of the brain, including the basal ganglia, which are involved both in regulating movement and processing challenging sentences. The subjects' favorite poems weakly activated a network in the brain associated with reading, but strongly activated the inferior parietal lobes, an area associated with recognition.

"Favorite poems appeared to be 'remembered' as much as or rather than 'read," Adam Zeman, an Exeter professor of cognitive and behavioral neurology, explains in an email.

Yet another recent experiment, detailed in a 2015 article in the neuroscience journal Cortex, University of Liverpool researchers used an fMRI to scan the brains of subjects while they read various passages of poetry and prose, in an effort to find what parts of the brain were involved in "literary awareness" — the capacity to think about and find meaning in a complex text. In half of the examples, the final line was an unexpected twist that Philip Davis, a professor and director of the school's Institute of Psychology, Health and Society, refers to as an "a-ha moment." (One example: William Wordsworth's 1799 poem "She Dwelt Among the Untrodden Ways," about a recluse who died in seclusion, in which the narrator drops a hint that he may have been her unrequited lover.) The subjects rated the passages on how poetic they seemed and whether or not the last lines led them to reappraise the meaning — a measure of literary awareness.

"We believe that this is the first fMRI that examines the unfolding effects of moving from line to line, and the consequences in terms of what we call literary awareness as compared to more automatic and literal-minded processing of meaning," says Davis in an email. "The poetic work triggered different parts of the brain related to non-automatic processing of meaning, leading to increased lively activation of mind and a simultaneous sense of psychological reward."

But the research also suggests that reading or listening to poetry is useful for something besides just rousing our emotions and elevating our souls. The same mental skills that we exercise in struggling to understand T.S. Eliot's "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock " — i.e., flexible thinking and the ability to ponder multiple meanings — also help us to navigate unpredictable events and make choices in our everyday lives.

"The calling into activation of literary awareness may have a significant effect in challenging our default mind-set," Davis says. He thinks that if more people read poetry and got accustomed to pondering meaning, "it would make a difference to their capacity to think with more alertness to excite surprise and change."

Advertisement