It's a tale as old as crime and as cold as the heart of the sea: One dark and moonless night, an innocent young luxury liner wanders into a dangerous North Atlantic alley -- a known haunt of iceberg gangs. Heedless of warnings about this dangerous element, the ship hurries onward, possessed of that sense of invulnerability to which the young are prone.

On any other night, the White Star liner might have made it through unscathed, but tonight -- April 14, 1912 -- the icebergs are out in force, and the infamous, inevitable rendezvous with destiny occurs. The Titanic succumbs to its wounds within hours, leaving around 1,500 people to die in the icy waters on April 15, 1912.

Advertisement

Case closed -- or is it? What if the iceberg was just a patsy for a larger, celestial conspiracy? Who -- or what -- was ultimately to blame for the Titanic's tragic maiden voyage? Should we blame it on Rio? The rain? The bossa nova? Or was it an act of lunar-cy?

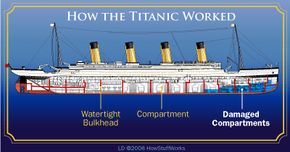

Armchair sleuths and industry experts have reopened the case countless times. Over the past century, researchers, authors and filmmakers have blamed the incident on everyone from White Star management and Belfast's Harland and Wolff shipyard to Captain E. J. Smith and helmsman Robert Hitchins. But there's a difference between proximate (close, direct) cause and ultimate cause. The proximate cause of the Titanic sinking? Filling with too much water. The ultimate cause? An iceberg opening holes in its side.

Ultimate causes tend to chain backward to other causes, and still others, inviting more questions along the way. What forces, for example, brought that iceberg to that particular stretch of sea at that fateful moment?

According to one hypothesis advanced by a team of astronomers from Texas State University-San Marcos, the iceberg might have been the button man, but our celestial companion was the one who ordered the hit. More than that, the moon had accomplices.

Granted, our nearest neighbor has an airtight alibi: It was roughly a quarter of a million miles away at the time. In fact, the Titanic sank on a moonless night. Why was the moon concealing its face? What did it have to hide?

It's time to crack this coldest of cold cases.

Advertisement