In the 1990s, planetary scientists started becoming aware that our planet could become a prime target in the cosmic shooting gallery. There was a growing realization that, over geological timescales, Earth gets hit by large asteroids and comets rather frequently; however, unlike the moon's obvious craters, Earth's atmosphere is very efficient at eroding the evidence of massive impacts.

Scientists had previously identified the infamous Chicxulub Crater buried under the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico and linked it with the Cretaceous-Tertiary (K-T) boundary – a rocky layer that was created around the time of a mass extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. At the same time, astronomers were discovering more and more large chunks of space rock zooming around our sun. It started to become clear that it isn't a question of if we're going to get hit by a marauding space rock again but rather when.

Advertisement

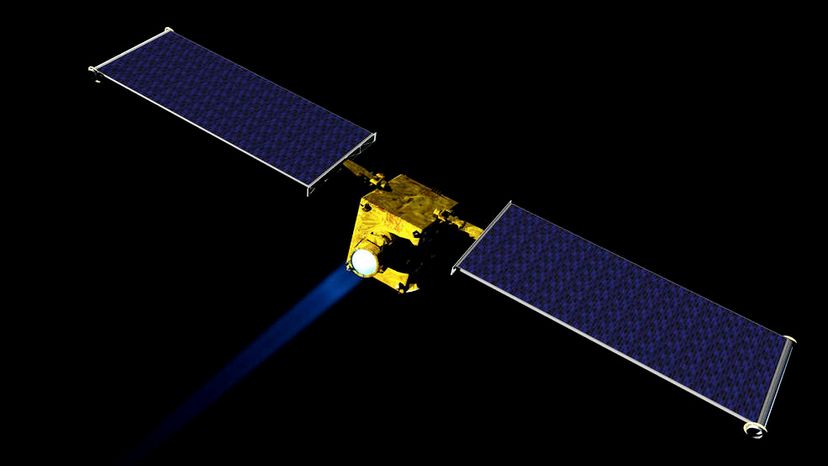

Inspired by the realization that asteroids could pose a threat, Andy Cheng started pondering the worst-case scenario: If we discovered an incoming asteroid, what could we do to prevent it from hitting Earth?

"For the first 20 years of working on this problem, we had to be really careful. People's reactions on hearing about this were 'are you serious?' We had to overcome the so-called giggle factor, but we're past that now," says Cheng, who works at The Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland.

Advertisement