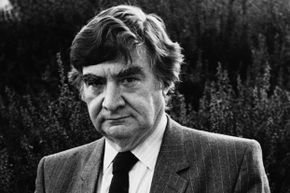

If America had a museum dedicated to its gullibility, out in front there would be a statute of Alan Abel, who was perhaps the foremost perpetrator of hoaxes in history. Back in the 1950s, Abel -- a jazz drummer turned performance artist -- conned the public and news media into thinking that his Society for Indecency to Naked Animals, or SINA, which campaigned for horses, dogs and other creatures to wear clothing, was a bona fide movement.

Since then, he's pulled Americans' legs too many times to count. He appeared on daytime TV in the guise of "Dr. Herbert Strauss," a physician who made it seem believable that people could survive on a diet of nothing but human hair, and planted a slew of newspaper stories including one about "euthanasia cruises," in which a cruise ship with a specially-greased deck would dump despondent passengers into the ocean. He even once convinced the eminent New York Times that he himself had died, compelling the embarrassed newspaper to print a correction to his lengthy obituary two days later [source: Keohane].

Advertisement

Abel's career is just part of a mountain of evidence of how easily we can be fooled into believing things that aren't true. You'd think that the advent of the Internet, which makes it easy to look up information on just about any subject, would help protect us from being conned. But instead, it only seems to have made things worse. Today, a digital hoax can spread across the planet in a few mouse clicks. It makes The Who's classic rock tune, "Won't Get Fooled Again," seem like a cruel taunt to us all.

Can we avoid getting fooled again? Maybe not, but experts say we can learn to spot tell-tales clues that we're being conned, and develop vetting methods that compensate for our tendency to believe what we hear, read or see. Here are 10 tips for telling fact from fiction.