The more you know about your memory, the better you'll understand how you can improve it. Here's a basic overview of how your memory works and how aging affects your ability to remember.

Your baby's first cry...the taste of your grandmother's molasses cookies...the scent of an ocean breeze. These are memories that make up the ongoing experience of your life -- they provide you with a sense of self. They're what make you feel comfortable with familiar people and surroundings, tie your past with your present, and provide a framework for the future. In a profound way, it is our collective set of memories -- our "memory" as a whole -- that makes us who we are.

Advertisement

Most people talk about memory as if it were a thing they have, like bad eyes or a good head of hair. But your memory doesn't exist in the way a part of your body exists -- it's not a "thing" you can touch. It's a concept that refers to the process of remembering.

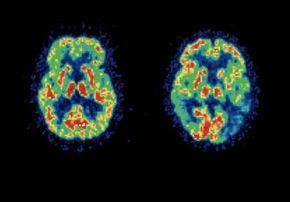

In the past, many experts were fond of describing memory as a sort of tiny filing cabinet full of individual memory folders in which information is stored away. Others likened memory to a neural supercomputer wedged under the human scalp. But today, experts believe that memory is far more complex and elusive than that -- and that it is located not in one particular place in the brain but is instead a brain-wide process.

Do you remember what you had for breakfast this morning? If the image of a big plate of fried eggs and bacon popped into your mind, you didn't dredge it up from some out-of-the-way neural alleyway. Instead, that memory was the result of an incredibly complex constructive power -- one that each of us possesses -- that reassembled disparate memory impressions from a web-like pattern of cells scattered throughout the brain. Your "memory" is really made up of a group of systems that each play a different role in creating, storing, and recalling your memories. When the brain processes information normally, all of these different systems work together perfectly to provide cohesive thought.

What seems to be a single memory is actually a complex construction. If you think of an object -- say, a pen -- your brain retrieves the object's name, its shape, its function, the sound when it scratches across the page. Each part of the memory of what a "pen" is comes from a different region of the brain. The entire image of "pen" is actively reconstructed by the brain from many different areas. Neurologists are only beginning to understand how the parts are reassembled into a coherent whole.

If you're riding a bike, the memory of how to operate the bike comes from one set of brain cells; the memory of how to get from here to the end of the block comes from another; the memory of biking safety rules from another; and that nervous feeling you get when a car veers dangerously close, from still another. Yet you're never aware of these separate mental experiences, nor that they're coming from all different parts of your brain, because they all work together so well. In fact, experts tell us there is no firm distinction between how you remember and how you think.

This doesn't mean that scientists have figured out exactly how the system works. They still don't fully understand exactly how you remember or what occurs during recall. The search for how the brain organizes memories and where those memories are acquired and stored has been a never-ending quest among brain researchers for decades. Still, there is enough information to make some educated guesses. The process of memory begins with encoding, then proceeds to storage and, eventually, retrieval.

On the next page, you'll learn how encoding works and the brain activity involved in retrieving a memory.

Advertisement